|

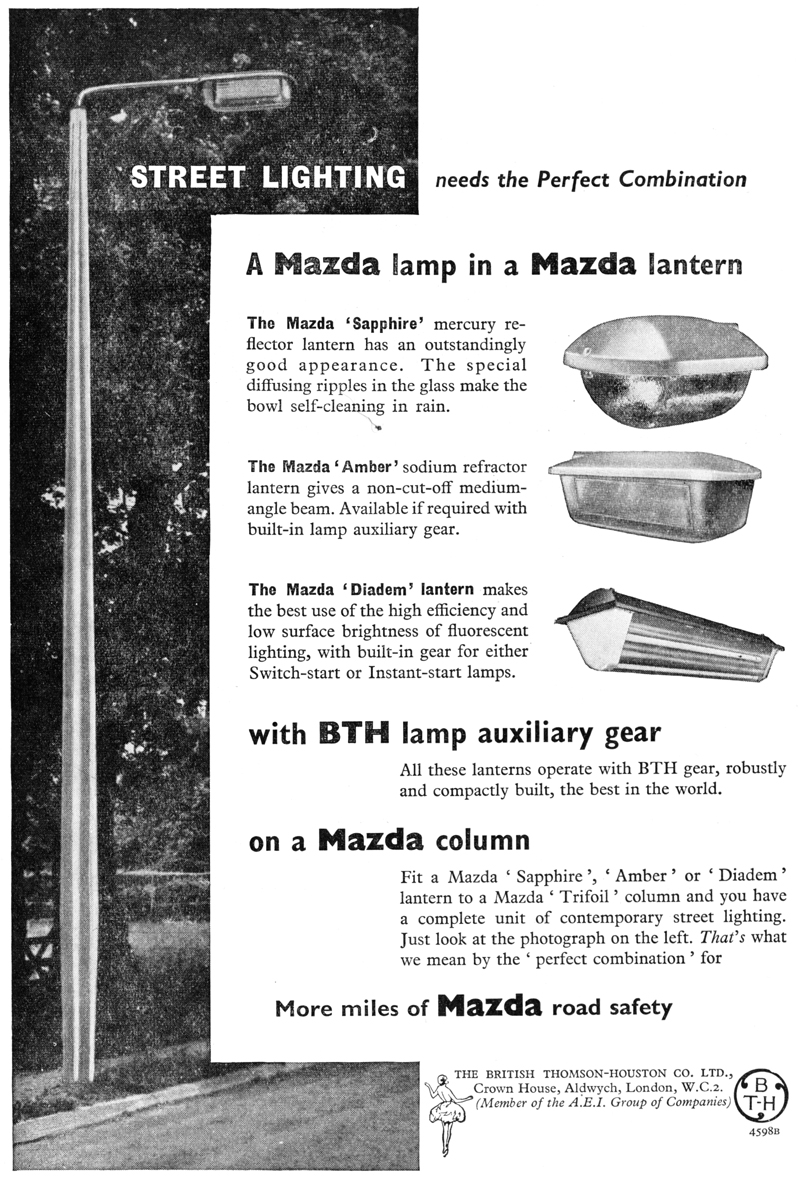

bth amber mk iv a10600

Genre: Enclosed Horizontal Traverse Low Pressure Sodium Lantern

The low pressure sodium discharge lamp was developed by Philips in 1932. After two successful trial installations

(including the first low pressure sodium installation in the UK along the Purley Way, Croydon) the first commercial installation

was installed by Liverpool Council in 1933 using specially commissioned lanterns from Wardle.

The development of lanterns continued through the 1930s and accelerated when it was determined that the lampís brightness and

its long length made it less susceptible to glare. Lanterns with bare bulbs suspended over an overhead reflector (the so-called "seagull" lanterns)

quickly followed. Glass manufacturers were initially slow as the first plate refractors for low pressure sodium lamps didnít appear

until the end of the decade.

The advantages and disadvantages of low pressure sodium were readily debated, especially when an alternative (the medium and high

pressure mercury discharge lamp) was also available. The monochromatic light was considered especially useful for arterial

and traffic routes, the lampís shape cast a wide beam across the road surface, the light was also considered more penetrating

in foggy conditions and it was the most efficient light source being manufactured. However, the light was also considered

inappropriate for high streets, promenades, civic areas and residential streets and so some lighting engineers

restricted its use to traffic routes only. Therefore low pressure sodium became known as "the driversí lamp."

The arrival of plate glass refractors resulted in large lanterns made of metal frames enclosing heavy glass sheets.

These bulky lanterns continued to be made into the 1950s until being usurped by lanterns with plastic bowls and

machined or moulded plastic refractor plates. The lanterns were still large; the size dictated by the bulky

control gear, but their design and construction was becoming simpler.

The 1950s and 1960s saw huge improvements in the construction and efficacy of low pressure sodium. Early two-piece

designs (dubbed SO) were replaced by the one-piece, more efficient integral design (called the SOI). The development of

linear sodium (SLI) broke the one hundred lumens per watt barrier, lead to a radical rewriting of the British Standards

of street lighting and prompted the development of new families of streamlined lanterns. But it wasnít until the arrival

of a new heat-reflecting technology (called SOX) that a cheap family of extremely efficient bulbs became available.

The energy crisis of the 1970s saw a rethink in street lighting and lamp efficiency became dominant when fuel was both

in short supply and expensive. This saw the large scale removal of colour corrected high pressure mercury, fluorescent and

ancient tungsten lamps by low pressure sodium replacements. The old arguments that the smoky-orange lamps were inappropriate

for residential areas no longer applied. By the end of the 1980s, low pressure sodium was the dominant street lighting lamp used in the UK.

The use of low pressure sodium came under scrutiny again. High pressure sodium, finally developed as a viable technology in the

1960s, was coming of age and offered a compromise of slightly less efficacy with better colour rendering. Questions were

being asked about the physiology of the eye and visual adaptation under low lighting levels; previously the wavelength

of low pressure sodium had been deemed the most suitable, but research now suggested that the eye responded better to white

light. Concerns were raised about light pollution and the low pressure sodium lamp was seen to be the chief culprit

(although it was more to do with older non-cutoff and semi-cutoff optical designs rather than the lamp itself).

By the turn of the century, the age of low pressure sodium was seen as coming to an end. Research in white light technologies,

especially metal halide and a renewed interest in compact fluorescent coupled with the advantages of using white light at

low lighting levels, saw the end of the low pressure sodium lampís dominance. Its use was discouraged in the specifications,

lantern manufacturers started to wind down their production and bulb manufacturers followed suit.

By the end of the first decade of the 2000s, low pressure sodium was in stark decline, and less and less of the UKís

streets were being lit by its characteristic orange glow.

Name: BTH Amber MK IV A10600

Date: Late 1950s - Early 1960s

Dimensions: Length: 28", Width: 14", Height: 10"

Light Distibution: Non Cut-Off Medium Beam (BSCP 1004 Part One:1952)

Lamp: 140W (later 90W) SOX

History

|

The Amber was the name given to the family of BTH's low-pressure

sodium lanterns. BTH gave their lanternís purely functional names

(a trait which continued to successor companies AEI and Atlas),

so the name continued for over a decade as the lantern evolved. The range followed the classic

design of post-war lantern design: starting with a relatively sleek lantern with an aluminium

canopy and Perspex bowl with refractor plates, evolving into much larger lantern designed to

carry the heavy gear of the time.

The Amber MK III and MK IV became classic designs, installed in

large numbers across the country in the second half of the 1950s. The MK IV

became especially successful, being accepted by the Council of Industrial Design for Design Review,

and successfully retained the lantern's handsome profile and increased its ease of use

(by replacing the large knurled screw which held the bowl with far more user-friendly toggle catches).

The lantern was retained in the range during the "great reorganisation" of BTH

with its sister companies, as AEI consolidated and rebadged its disparate

companies. It was eventually discontinued in the early 1960s, replaced by another lantern called

Amber, which radically altered all aspects of the design, and removed any family

resemblance (this lantern eventually becoming known as the Alpha 9).

|

Popularity

The Amber MK IV series was popular throughout the country.

Identification

The lantern is easily identified by curved aluminium canopy and deep curved bowl

with large plate refractors. The MK IV also had steel toggles on the

traffic facing side of the lantern which differentiated it from earlier versions

in the range. The BTH logo was embossed on the underside of the canopy

(not on the top) and a sticker identified the maker and the lantern's catalogue number.

Optical System

The light flux was controlled by two large Perspex refractor plates which were stuck on

either side of the bowl. These produced a medium-angle beam in accordance with BCSP 1004:1952.

The underside of the aluminium canopy acted as a secondary reflector system but it was not

painted white and there were no fixing screws for white plastic over-reflectors

(as there was in the MK III).

The lamp was mounted low in the base of the bowl so optional gear could be fitted.

Gear

According to adverts, the lantern could be supplied with or without gear. This affected

the overall design of the lantern resulting in its characteristic deep bowl and low mounted lamp.

The BTH Amber MK IV A10600 In My Collection

|

|

facing profile

The BTH Amber MK IV was a popular lantern and was installed in many towns and

cities throughout the UK. It was the principle main road lantern in Cambridge where this example was installed.

|

|

|

|

front profile

The bowl was large and deep to accommodate the large leak transformers and condensers of the 1950s.

The ends of the bowl were slightly textured to facilitate extra diffusion of the light.

|

|

|

|

trailing profile

Despite many years of service, the lantern was still in good condition although the Perspex bowl had gone opaque with

age. The bowl was was made of pressed Perspex with separate refractor plates and separate bowl hinges (both of which

were glued on).

|

|

|

|

canopy

The canopy was a heavy casting of aluminium alloy. It carried the recesses for the bowl toggle clips

and extrusions for the bowl hinges.

|

|

|

|

logo

There were no maker's marks or logos on the top of the canopy. The large BTH logo which was so

prominent on the previous MK III model was now cast into the underside of the canopy.

At some point during its service, the canopy was drilled to accommodate a photoelectric cell.

|

|

|

|

pedestrian view

The two large brass toggle catches engaged with two moulded Perspex blocks which were stuck onto the bowl

separately. This was another modification of the previous MK III design which used a metal bowl

ring to hold the bowl.

|

|

|

|

vertical

The bottom of the bowl was unadorned allowing the flux from the lamp to illuminate

the area around the base of the column.

|

|

|

|

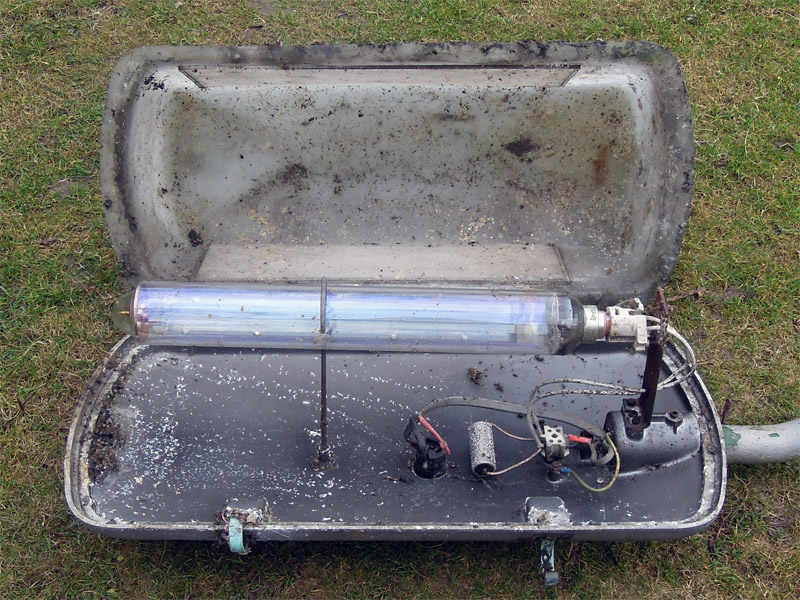

interior

The interior of the lantern was extremely basic and just featured the necessary drilled holes to support

the lamp assembly, lamp support, earth screw, terminal block and fixing screws. There were no fixing points

for any gear or optional reflector plates suggesting this was the basic model, and a different casting was

used for the gear version.

The BTH logo was now on the inside of the canopy. A sticker formerly gave the maker's

information and the lanternís model number, A10600, was stamped into the metal besides it.

The sticker had almost completely disintegrated when the lantern was saved, but the model number remained clear.

The sticker stated:

MADE IN  ENGLAND ENGLAND

LIGHTING EQUIPMENT

CAT NO: A 10600

The original neoprene gasket had mostly perished and was replaced with a new one.

An optional capacitor was fitted across the lamp contacts. This was a non-standard radio interference suppression

capacitor Ė I doubt it was part of the original lantern and was probably fitted in service. It's the first time I've

seen one of these capacitors in a low-pressure sodium lantern; they could normally be found in fluorescent lanterns.

|

BTH Amber MK IV A10600: As Aquired

This lantern was originally installed along Chesterton Road, Cambridge. It was located outside the Job Centre.

I also recsued the original BTH leak transformer and BTH condensor from the base of the column. The condenser

was stamped 1952.

The lantern was aquired in 2017 when the lighting was replaced as part of the Cambridgeshire/Northamptonshire PFI.

My thanks to Balfour Beatty who gave me permission to remove these lanterns.

The shot shows the interior of the lantern before restoration. A new gasket was fitted (the original had disappeared)

and the lantern was given a thorough clean.

|