|

Philips SXK 55 (MI 80)

Genre: Enclosed Horizontal Traverse Low Pressure Sodium Lantern

The low pressure sodium discharge lamp was developed by Philips in 1932. After two successful trial installations

(including the first low pressure sodium installation in the UK along the Purley Way, Croydon) the first commercial installation

was installed by Liverpool Council in 1933 using specially commissioned lanterns from Wardle.

The development of lanterns continued through the 1930s and accelerated when it was determined that the lampís brightness and

its long length made it less susceptible to glare. Lanterns with bare bulbs suspended over an overhead reflector (the so-called "seagull" lanterns)

quickly followed. Glass manufacturers were initially slow as the first plate refractors for low pressure sodium lamps didnít appear

until the end of the decade.

The advantages and disadvantages of low pressure sodium were readily debated, especially when an alternative (the medium and high

pressure mercury discharge lamp) was also available. The monochromatic light was considered especially useful for arterial

and traffic routes, the lampís shape cast a wide beam across the road surface, the light was also considered more penetrating

in foggy conditions and it was the most efficient light source being manufactured. However, the light was also considered

inappropriate for high streets, promenades, civic areas and residential streets and so some lighting engineers

restricted its use to traffic routes only. Therefore low pressure sodium became known as "the driversí lamp."

The arrival of plate glass refractors resulted in large lanterns made of metal frames enclosing heavy glass sheets.

These bulky lanterns continued to be made into the 1950s until being usurped by lanterns with plastic bowls and

machined or moulded plastic refractor plates. The lanterns were still large; the size dictated by the bulky

control gear, but their design and construction was becoming simpler.

The 1950s and 1960s saw huge improvements in the construction and efficacy of low pressure sodium. Early two-piece

designs (dubbed SO) were replaced by the one-piece, more efficient integral design (called the SOI). The development of

linear sodium (SLI) broke the one hundred lumens per watt barrier, lead to a radical rewriting of the British Standards

of street lighting and prompted the development of new families of streamlined lanterns. But it wasnít until the arrival

of a new heat-reflecting technology (called SOX) that a cheap family of extremely efficient bulbs became available.

The energy crisis of the 1970s saw a rethink in street lighting and lamp efficiency became dominant when fuel was both

in short supply and expensive. This saw the large scale removal of colour corrected high pressure mercury, fluorescent and

ancient tungsten lamps by low pressure sodium replacements. The old arguments that the smoky-orange lamps were inappropriate

for residential areas no longer applied. By the end of the 1980s, low pressure sodium was the dominant street lighting lamp used in the UK.

The use of low pressure sodium came under scrutiny again. High pressure sodium, finally developed as a viable technology in the

1960s, was coming of age and offered a compromise of slightly less efficacy with better colour rendering. Questions were

being asked about the physiology of the eye and visual adaptation under low lighting levels; previously the wavelength

of low pressure sodium had been deemed the most suitable, but research now suggested that the eye responded better to white

light. Concerns were raised about light pollution and the low pressure sodium lamp was seen to be the chief culprit

(although it was more to do with older non-cutoff and semi-cutoff optical designs rather than the lamp itself).

By the turn of the century, the age of low pressure sodium was seen as coming to an end. Research in white light technologies,

especially metal halide and a renewed interest in compact fluorescent coupled with the advantages of using white light at

low lighting levels, saw the end of the low pressure sodium lampís dominance. Its use was discouraged in the specifications,

lantern manufacturers started to wind down their production and bulb manufacturers followed suit.

By the end of the first decade of the 2000s, low pressure sodium was in stark decline, and less and less of the UKís

streets were being lit by its characteristic orange glow.

Name: Philips SXK 55 (MI 80)

Date: Early 1970s - Late 1980s

Dimensions: Length: TBA, Width: TBA, Height: TBA

Light Distibution: Semi Cut-Off (BS 4533:1976)

Lamp: 35W-55W SOX

History

If a UK lighting engineer was asked about Philips in the early 1960s, then he wouldíve only known

them for bulb production and the invention of the low pressure sodium discharge lamp in the early 1930s.

By the mid-1960s, the firm had joined forces with ELECO and were advertising their own range of lanterns;

but whether these were developed by ELECO or Philips still isnít known.

The early 1970s saw a radical change for Philips in the UK when they started producing their own

range of lanterns. A comprehensive advertising campaign (which often saw a series of adverts placed in lighting

publications) and contracts to light the UKís motorway network saw the firm offering a whole range of newly designed lanterns.

The Philips MI80 was one of this new range, replacing the earlier Philips MI8

(another ambiguous lantern as itís believed it was designed by Phosco and sold by them as the P224).

The MI80 featured a distinctive aluminium canopy with the refractor bowl matching the luminarie's

characteristic profile. The similar MI50 was designed to take the smaller 35W lamp.

The lantern was also designed as a security lighting option. As it was a compact model (both gear and photo cell were included),

the security option simply included a mounting bracket. The catalogue number for this package was

SXK 55; this was reflected on the sticker inside the lantern, but this was the only difference

between the security SXK 55 and the street MI80.

It remained on the catalogue for over a decade, but was eventually replaced by the Philips MI36.

This offered the same optical system (the bowl was the same), gear and photo cell, but the canopy was made of plastic and

variable mounting allowed both side-entry and post-top options.

Popularity

This family of low pressure sodium lanterns were extremely popular throughout the UK, although the later

Philips MI36 was installed in far greater numbers. The Philips

MI80 was the rarest of the group.

Identification

The lanternís curved canopy, relatively deep similarly curved bowl and stainless steel bowl clips made it an

easy lantern to identify. From a distance, the lantern could be confused with the Simplex Gemini

but the refractor patterns on the bowls were sufficiently different to differentiate between them when closer.

Optical System

The primary optical system comprised of two plate refractors positioned either side of the bulb. As the low pressure

sodium lantern already casts a wide beam in azimuth, the horizontal refractors simply alter the flux elevation by

fashioning two main beams in a semi-cut-off distribution (in accordance with BS 4533:1976).

The underside of the gear tray is painted white and acts as a secondary reflector.

The exterior of the bowl is smooth to facilitate easy cleaning.

Gear

The gear is mounted on a steel sheet which is secured to the lantern by means of four screws. The base of this

gear tray is painted white and acts as a secondary reflector.

The Philips SXK 55 (MI 80) In My Collection

|

|

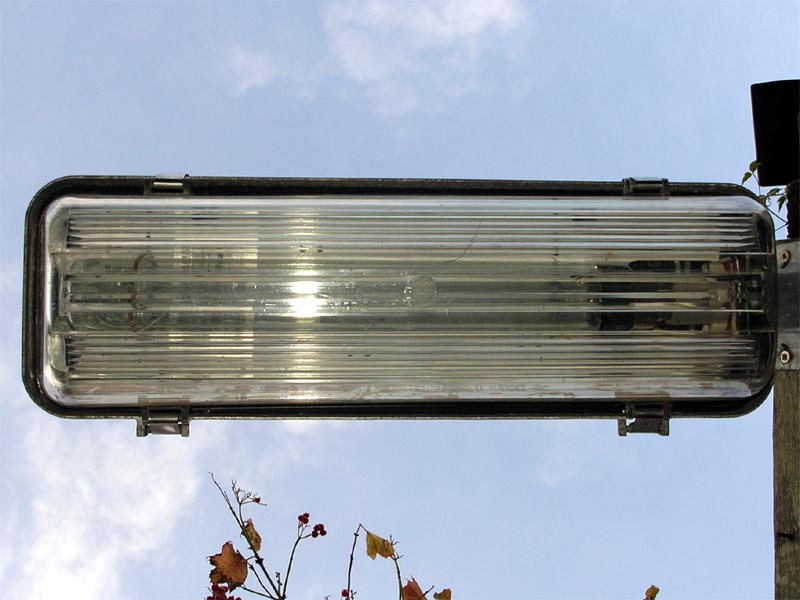

facing profile

I rescued two of these lanterns from a derelict factory in Cambridgeshire. They were oddly installed as they were

used to floodlight the delivery yard, mounted low on some metal poles attached to a diesel tank

and tilted almost horizontally.

|

|

|

|

front profile

Both lanterns were in good condition although, oddly, the interior wiring had been cut.

I repaired this in one lantern and offered the other as a swap.

|

|

|

|

trailing profile

This view clearly shows how the canopy profile matched the bowl profile, presenting a relatively

bulky lantern for the early 1970s. The bulge in the canopy was designed for top-entry lanterns but

remained undrilled for these side-entry versions.

|

|

|

|

canopy

The photocell was included as standard. The stainless steel hinges both clipped the bowl

firmly to the lantern against a rubber gasket and could be easily removed for cleaning.

|

|

|

|

logo

Oddly the lantern doesnít feature the Philips

name and logo embossed on the canopy. This was standard for their lanterns,

even the later ones made from GRP.

|

|

|

|

pedestrian view

The refractor prisms were moulded directly into the bowl; there wasnít the idea of a section of

refractor plates which was common in earlier lanterns from the 1950s through to the 1960s.

|

|

|

|

vertical

The refractor pattern continued on the base of the bowl to spread the light beneath the lantern

in accordance with the strict BS 1788:1964.

|

|

|

|

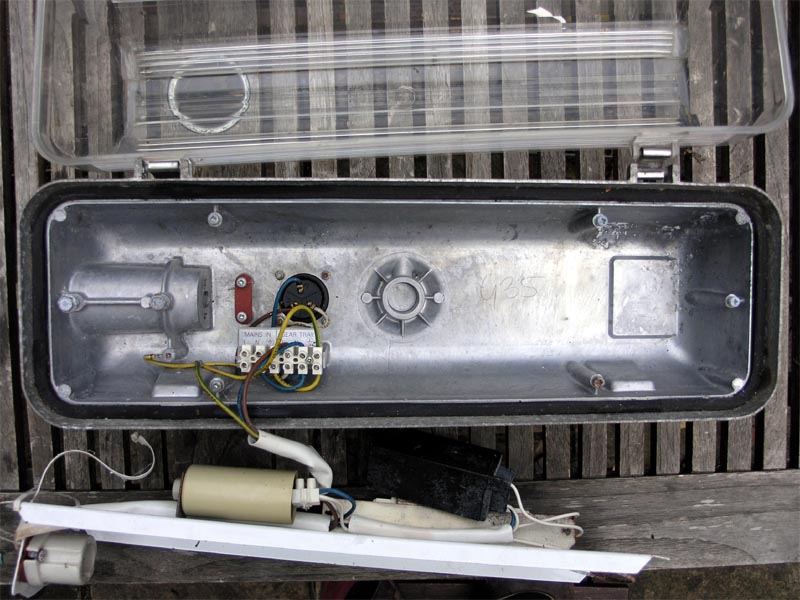

open bowl

The bowl swung open on its stainless steel clips and could be easily detached for cleaning (one of the better

and easier designs to deal with). The underside of the gear tray can be seen, painted white to act as a

secondary reflector. The lanternís identifying sticker and model number can also be seen.

|

|

|

|

interior #1

The interior of the canopy featured two locking bolts, cable clamp, terminal strip (with helpful labels)

and four screws to hold the gear tray in place.

|

|

|

|

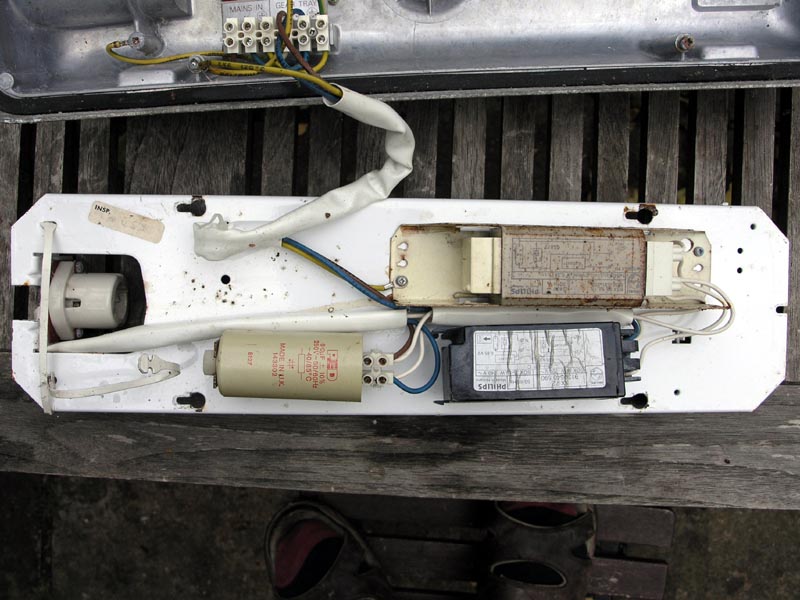

interior #2

The gear tray held all the gear required to run a 35W or 55W SOX lamp. Included were a Philips BSX 355 L16

ballast, a PED power correction capacitor (rated at 8.0uF and dated 1981) and a Philips SX 72

ignitor.

|

Philips SXK 55 (MI 80): Night Burning

Philips SXK 55 (MI 80): As Aquired

This was the first streetlight I obtained, rescuing it from the derelict Ross Foods site in Girton, Cambridge before demolition.

The SXK 55 was a commercial security light package; it included a complete lantern (gear-in-head with photocell) with a mounting

bracket. Hence they're usually found in car parks and in factory areas.

It's actually more commonly known as a Philips MI 80 lantern.

|