|

Siemens Ediswan Orson Lantern

Genre: Enclosed Horizontal Traverse Low Pressure Sodium Lantern

The low pressure sodium discharge lamp was developed by Philips in 1932. After two successful trial installations

(including the first low pressure sodium installation in the UK along the Purley Way, Croydon) the first commercial installation

was installed by Liverpool Council in 1933 using specially commissioned lanterns from Wardle.

The development of lanterns continued through the 1930s and accelerated when it was determined that the lampís brightness and

its long length made it less susceptible to glare. Lanterns with bare bulbs suspended over an overhead reflector (the so-called "seagull" lanterns)

quickly followed. Glass manufacturers were initially slow as the first plate refractors for low pressure sodium lamps didnít appear

until the end of the decade.

The advantages and disadvantages of low pressure sodium were readily debated, especially when an alternative (the medium and high

pressure mercury discharge lamp) was also available. The monochromatic light was considered especially useful for arterial

and traffic routes, the lampís shape cast a wide beam across the road surface, the light was also considered more penetrating

in foggy conditions and it was the most efficient light source being manufactured. However, the light was also considered

inappropriate for high streets, promenades, civic areas and residential streets and so some lighting engineers

restricted its use to traffic routes only. Therefore low pressure sodium became known as "the driversí lamp."

The arrival of plate glass refractors resulted in large lanterns made of metal frames enclosing heavy glass sheets.

These bulky lanterns continued to be made into the 1950s until being usurped by lanterns with plastic bowls and

machined or moulded plastic refractor plates. The lanterns were still large; the size dictated by the bulky

control gear, but their design and construction was becoming simpler.

The 1950s and 1960s saw huge improvements in the construction and efficacy of low pressure sodium. Early two-piece

designs (dubbed SO) were replaced by the one-piece, more efficient integral design (called the SOI). The development of

linear sodium (SLI) broke the one hundred lumens per watt barrier, lead to a radical rewriting of the British Standards

of street lighting and prompted the development of new families of streamlined lanterns. But it wasnít until the arrival

of a new heat-reflecting technology (called SOX) that a cheap family of extremely efficient bulbs became available.

The energy crisis of the 1970s saw a rethink in street lighting and lamp efficiency became dominant when fuel was both

in short supply and expensive. This saw the large scale removal of colour corrected high pressure mercury, fluorescent and

ancient tungsten lamps by low pressure sodium replacements. The old arguments that the smoky-orange lamps were inappropriate

for residential areas no longer applied. By the end of the 1980s, low pressure sodium was the dominant street lighting lamp used in the UK.

The use of low pressure sodium came under scrutiny again. High pressure sodium, finally developed as a viable technology in the

1960s, was coming of age and offered a compromise of slightly less efficacy with better colour rendering. Questions were

being asked about the physiology of the eye and visual adaptation under low lighting levels; previously the wavelength

of low pressure sodium had been deemed the most suitable, but research now suggested that the eye responded better to white

light. Concerns were raised about light pollution and the low pressure sodium lamp was seen to be the chief culprit

(although it was more to do with older non-cutoff and semi-cutoff optical designs rather than the lamp itself).

By the turn of the century, the age of low pressure sodium was seen as coming to an end. Research in white light technologies,

especially metal halide and a renewed interest in compact fluorescent coupled with the advantages of using white light at

low lighting levels, saw the end of the low pressure sodium lampís dominance. Its use was discouraged in the specifications,

lantern manufacturers started to wind down their production and bulb manufacturers followed suit.

By the end of the first decade of the 2000s, low pressure sodium was in stark decline, and less and less of the UKís

streets were being lit by its characteristic orange glow.

Name: Siemens Ediswan Orson Lantern

Date: Late 1950s - Early 1960s

Dimensions: Length: TBA, Width: TBA, Height: TBA

Light Distibution: Non Cut-Off (BSCP 1004 Part Two:1956)

Lamp: 85W SO/H (55W SOX)

History

|

|

By the end of the 1950s and the start of the 1960s, many firms were losing their identities in the huge

mergers and take-overs which almost became commonplace during this period. Siemens (the UK company) and

Ediswan were merged together as Siemens Ediswan in the mid-1950s, part of the consolidation

of holding company AEI.

Siemens were best known for their pioneering fluorescent lanterns and had recently achieved huge success

with the Kuwait Unitary System: a family of slim-line fluorescent lanterns made from different numbers

of components parts. When merged with Siemens Ediswan, the firm continued with the Kuwait

range, but also scored a notable first with their developments for the new SLI/H sodium bulb: the Oline lantern.

The Orson lantern was its SO/H sibling, a lantern very much of its era. Its huge canopy supported the

equally massive leak transformer and bulky condenser whilst an equally huge bowl dwarfed the enclosed bulb and

supported two large plastic Perspex refractor plates.

This was perhaps the reason behind its unpopularity and subsequent rarity. It was simply too big; other lanterns

from other manufacturers (even with the huge gear of the era) were smaller, better designed and more streamlined.

And by the late 1950s and early 1960s, when the lantern was being mentioned in Public Lighting, it was already

almost antiquated.

The lantern disappeared when Siemens Ediswan was finally assimilated into AEI

and the ranges of the various constituent companies were rationalised. I suspect manufacturing of this lantern

stopped in favour of the Amber lantern (formerly produced by BTH).

|

Popularity

It was never a popular lantern. Apart from an installation in Bootle (mentioned in Public Lighting), a scheme

in Australia and road lighting for a factory in Inverness (where this example was rescued) then no

other installations are known.

Identification

Apart from its size, the lantern can also be identified by its tapered aluminium canopy, deep almost

featureless bowl and a single thumbscrew at the road-end of the lantern securing the bowl.

Optical System

The optical system is interesting as the bulb is positioned at the base of the bowl. The refractor plates are positioned

centrally and only form the main beams from light cast upwards by the bulb or from reflected light from the overhead

reflector. In this way, the overhead reflector is far more important in this lantern than it normally is in other low-pressure

sodium lanterns where the bulb is positioned in the centre of the refractor plates.

Gear

The lantern was designed to take the huge open-wound leak transformers and large condensers

of the 1950s. Much of its size was dictated by the bulk of these electrical components.

Siemens Ediswan Orson Lantern In My Collection

|

|

facing profile

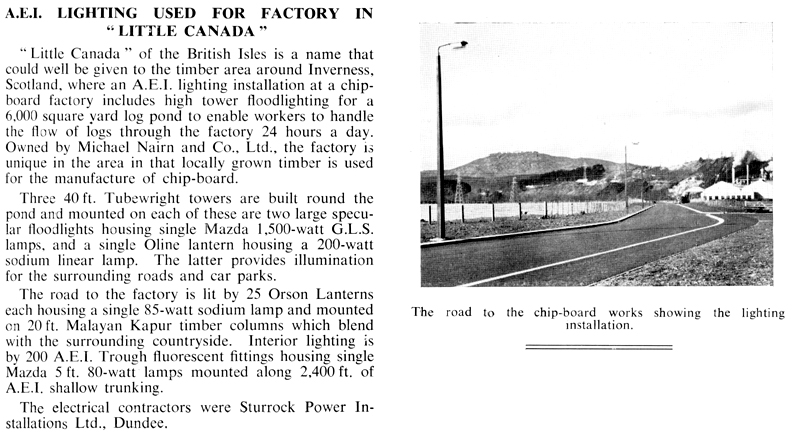

This lantern was installed on an approach road to a timber factor near Inverness in 1961. It was one

of an installation of twenty-five Orson lanterns and one Oline lantern;

the use of timber columns for the lanterns was of sufficient interest for Public Lighting to write about it.

|

|

|

|

front profile

The front profile clearly shows how enormous this lantern is. The deep bowl dwarfs the relatively

slimline canopy. The dark area in the canopy is the space for the huge 1950s control gear, hidden

underneath a separate over-reflector.

|

|

|

|

trailing profile

The bowl has been damaged during its years of service. It appears to have been used for target practise by

the local youths when the factory area became derelict. Over the years, the refractor plates became

unglued and were lying in the base of the bowl, which is why they escaped damage.

|

|

|

|

canopy

The canopy was smooth and featureless. There were no side clips either; the bowl being secured by

two large hinges on the path-side of the lantern, and a knurled screw at the other end.

|

|

|

|

logo

There were no makers marks or logos cast into the top of the canopy. This made initial identification difficult.

|

|

|

|

pedestrian view

There is a large hole in the path-side portion of the bowl but due to the rarity of this lantern (only three were saved)

then this damaged bowl will have to be retained. The only optical control is via the two refractor plates which are

glued onto each side of the bowl.

|

|

|

|

vertical

This shot again shows how large the lantern is. The 55W SOX bowl appears lost inside; the width of

the canopy being dictated by the dimensions of the original huge leak transformer.

|

|

|

|

interior #1

The interior of the canopy is very basic and rigid. There are mounting points for

the leak transformer, power correction capacitor, lamp holder assembly and over-reflector.

|

|

|

|

interior #2

A number "1832" and the hexagonal logo "ADC" are cast into the interior of the canopy but it isnít known what these refer to.

|

|

|

|

interior #3

This shot shows the open-coil leak transformer and power correction capacitor installed. The asbestos

wiring has been replaced.

The power correction capacitor was clearly manufactured by Siemens Ediswan as

the oval logo can be seen but the manufacturer of the leak transformer isnít known. There was an oval

mark where a sticker was once placed, and its shape suggests Siemens Ediswan made the leak transformer as well.

Older gear tends to work extremely well and the gear lit a new 55W SOX lamp after over fifty years of service.

|

|

|

|

interior #4

The final shot shows the interior of the lantern with the over-reflector in place. This thin white-painted

piece of steel also carries the lamp steady.

|

Siemens Ediswan Orson: As Aquired

A small installation of these lanterns was spotted by John Mitchell. They used to light the approach road to factory which was now

derelict. Interestingly, the columns were made of wood, with metal brackets supporting the lanterns.

John arranged the removal of three lanterns with the demolition firm in 2009. Amazingly one was still fitted with an 85W Siemens Ediswan SO/H bulb.

Unfortunately all three examples had limited bowl damage but this was acceptable given the rarity of the lanterns. John kept one for himself

and the other two were sold to collectors.

Identification of the lanterns was difficult. There was no maker's mark, no identification stickers and a small logo and number cast into the canopy simply

confused matters further. The gear (original open-wound leak transformer and capacator) had dark areas where the manufacturer's stickers were, and their

oval shape suggested Siemens Ediswan.

The only lantern which fitted the description was the Orson but I didn't have any pictures.

Amazingly, whilst looking through Public Lighting, I found a piece written about their installation. Not only did this finally identify the

lanterns, but it gave their installation date of 1961.

|