|

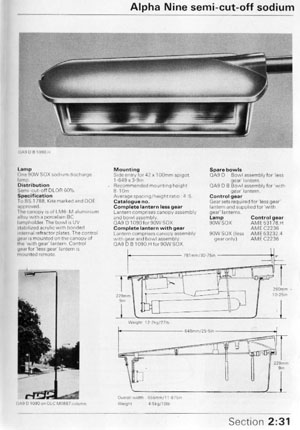

thorn emi alpha 9 (qa9 d 1090)

Genre: Enclosed Horizontal Traverse Low Pressure Sodium Lantern

The low pressure sodium discharge lamp was developed by Philips in 1932. After two successful trial installations

(including the first low pressure sodium installation in the UK along the Purley Way, Croydon) the first commercial installation

was installed by Liverpool Council in 1933 using specially commissioned lanterns from Wardle.

The development of lanterns continued through the 1930s and accelerated when it was determined that the lamp’s brightness and

its long length made it less susceptible to glare. Lanterns with bare bulbs suspended over an overhead reflector (the so-called "seagull" lanterns)

quickly followed. Glass manufacturers were initially slow as the first plate refractors for low pressure sodium lamps didn’t appear

until the end of the decade.

The advantages and disadvantages of low pressure sodium were readily debated, especially when an alternative (the medium and high

pressure mercury discharge lamp) was also available. The monochromatic light was considered especially useful for arterial

and traffic routes, the lamp’s shape cast a wide beam across the road surface, the light was also considered more penetrating

in foggy conditions and it was the most efficient light source being manufactured. However, the light was also considered

inappropriate for high streets, promenades, civic areas and residential streets and so some lighting engineers

restricted its use to traffic routes only. Therefore low pressure sodium became known as "the drivers’ lamp."

The arrival of plate glass refractors resulted in large lanterns made of metal frames enclosing heavy glass sheets.

These bulky lanterns continued to be made into the 1950s until being usurped by lanterns with plastic bowls and

machined or moulded plastic refractor plates. The lanterns were still large; the size dictated by the bulky

control gear, but their design and construction was becoming simpler.

The 1950s and 1960s saw huge improvements in the construction and efficacy of low pressure sodium. Early two-piece

designs (dubbed SO) were replaced by the one-piece, more efficient integral design (called the SOI). The development of

linear sodium (SLI) broke the one hundred lumens per watt barrier, lead to a radical rewriting of the British Standards

of street lighting and prompted the development of new families of streamlined lanterns. But it wasn’t until the arrival

of a new heat-reflecting technology (called SOX) that a cheap family of extremely efficient bulbs became available.

The energy crisis of the 1970s saw a rethink in street lighting and lamp efficiency became dominant when fuel was both

in short supply and expensive. This saw the large scale removal of colour corrected high pressure mercury, fluorescent and

ancient tungsten lamps by low pressure sodium replacements. The old arguments that the smoky-orange lamps were inappropriate

for residential areas no longer applied. By the end of the 1980s, low pressure sodium was the dominant street lighting lamp used in the UK.

The use of low pressure sodium came under scrutiny again. High pressure sodium, finally developed as a viable technology in the

1960s, was coming of age and offered a compromise of slightly less efficacy with better colour rendering. Questions were

being asked about the physiology of the eye and visual adaptation under low lighting levels; previously the wavelength

of low pressure sodium had been deemed the most suitable, but research now suggested that the eye responded better to white

light. Concerns were raised about light pollution and the low pressure sodium lamp was seen to be the chief culprit

(although it was more to do with older non-cutoff and semi-cutoff optical designs rather than the lamp itself).

By the turn of the century, the age of low pressure sodium was seen as coming to an end. Research in white light technologies,

especially metal halide and a renewed interest in compact fluorescent coupled with the advantages of using white light at

low lighting levels, saw the end of the low pressure sodium lamp’s dominance. Its use was discouraged in the specifications,

lantern manufacturers started to wind down their production and bulb manufacturers followed suit.

By the end of the first decade of the 2000s, low pressure sodium was in stark decline, and less and less of the UK’s

streets were being lit by its characteristic orange glow.

Name: Thorn EMI Alpha 9 (QA9 D 1090)

Date: 1960s - 1990s

Dimensions: Length: 25½", Width: 11 7/8", Height: 9"

Light Distibution: Non Cut-Off Medium Beam (BSCP 1004:1963, BS 1788:1964)

Lamp: 140W (later 90W) SOX

History

|

The Amber lantern range was first developed by British Thompson Houston (BTH) in the late

1940s for the low-pressure sodium (LPS) discharge lamp. BTH's naming was industrial and pragmatic, and

Amber perfectly described the orange light emitted by these lanterns. Another of their straight-forwardly-named

lanterns, the Residential, was essentially an Amber lantern fitted with fluorescent tubes for

residential and side-road lighting. These fluorescent lanterns were often tilted slightly to increase the

throw of light across the road.

The fully history of the final Amber lantern has yet to be discovered, but it was a curious design, with

the lamp held in a slanted position under the canopy, with the bowl following the same sloped angle. It is

thought that this design started off life in 1961 as a new version of the Residential with in-built

angled lamps, obviating the need for an angled bracket. The designers at Associated Electrical Industries (AEI) Lamps And Lighting – a

holding company that subsumed BTH and others in the late 1950s – simply reused the design for their new

low-pressure sodium lantern. Hence the last Amber had an extremely angular and tilted appearance – unlike

lanterns from other firms.

Thorn Lighting purchased a number of shares of AEI Lamps And Lighting in the early 1960s, allowing

them to make AEI's products under their own Atlas trademark. So, in the early part of the decade, the

AEI Amber was also sold as the Atlas Alpha 9. When Thorn became a majority shareholder in the

mid 1960s, they formed British Lighting Industries (BLI) to promote and sell all their products, and

the lantern was branded the BLI Alpha 9. By the end of the 1960s, Thorn bought

AEI Lamps And Lighting outright and the lantern was kept in production.

It was still sold as the BLI Alpha 9 for a short time, before Thorn reverted back to its Atlas trademark

in the 1970s and so the lantern was distributed with Atlas Alpha 9 stickers. By the next decade, the company

dropped the Atlas brand, and the lantern's final name became the Thorn Alpha 9 in the 1980s and beyond.

The result being that this quirky lantern had several different names and brandings:

AEI Amber, Atlas Alpha 9, BLI Alpha 9, or finally, the Thorn Alpha 9.

A version with gear was also made. This included a different canopy with was fitted with the necessary mounting points

for a small gear tray on which all the components were mounted. The bulky gear necessitated an elongated bowl

to be fitted. It had the angular lines as the more streamlined counterpart but with a much deeper bowl.

Despite its quirky design, it outlived Thorn's own homegrown medium-wattage LPS lantern, the

Thorn Alpha 1, and went on to become the firm's LPS lantern for main road use. It continued on catalogue into

the 2000s until demand for such lanterns – especially old bulky 1960s designs – started to wain and the lantern

was discontinued.

|

Popularity

The lantern missed the major relighting schemes of the immediate post-war decades so was not initially

used in large numbers. However, by the end of the 1960s, it became the lantern of choice for casual

replacements, lighting upgrade schemes and new roads. Therefore it became an extremely popular lantern

throughout the country, although often found sporadically installed in established installations.

Identification

The lantern's distinctive sloped profile and angular bowl made it an easy lantern to identify. The canopy

was never marked with the manufacturer's name or logo (both AEI and Thorn dropped this form of lantern identification)

but a sticker inside gave the lantern's name, maker, wattage and light distribution.

Optical System

The light flux was controlled by two large Perspex refractor plates which were stuck on

either side of the bowl. These produced a medium-angle beam in accordance with BSCP 1004:1963.

The interior of the canopy of the lantern was either painted a very light blue (Atlas) or white

(Thorn) to act as the secondary lighting system. No lugs or bosses were provided for the fitting of an

over-reflector.

Gear

Two styles of canopy were produced: one without the necessary fixing points for gear and one with the gear

mounting points. Lanterns fitted with gear often had deeper bowls to accomodate the gear.

the thorn emi alpha 9 (qa9 d 1090) in my collection

|

|

facing profile

The Thorn EMI Alpha 9 was a popular lantern of conventional design (canopy, plastic bowl with

refractors, easy access via a clip) but of unconventional appearance (angled canopy, sharp angled bowl, lamp

positioned with lamp holder at the roadside).

I obtained this lantern in the mid 2000s when it was removed from Long Road, Cambridge. It originally stood on

the railway bridge and had been crudely converted to a cut-off lantern by obscuring the refractors with duct tape.

|

|

|

|

front profile

Despite its sharp profile, the lantern actually had gently sloping sides and a reflectively

large base area. The angled reflectors created the main beams for illuminating the road, whilst the gently

curved base spread the flux below the lantern, ensuring the road had a uniform luminated appearance.

|

|

|

|

trailing profile

After many years of service, the lantern was still in good condition, and only required a thorough clean.

The bowl was made from acrylic as it was not starting to discolour.

|

|

|

|

canopy

The canopy was a heavy casting aluminium alloy. Like all later AEI/Thorn lanterns, it

did not have the manufacturer's name cast into the canopy.

|

|

|

|

logo

The bowl was angled by a hinge at the roadside of the lantern, being secured by a clip at the pavement end.

This ensured the bowl swung out over the road – a design choice emphasised by BS 1788:1964. (If the bowl was hinged

at the pavement side of the lantern then there was a change that it would become unclipped and smash into the column).

|

|

|

|

pedestrian view

The bowl could be easily removed by pulling it upwards from the hinge. This helped cleaning and/or replacement.

In this shot, the tensioned clip which held the bowl securely at the pavement side of the lantern, can

be clearly seen.

|

|

|

|

vertical

The base of the bowl wasn't obscured in any way – the gentle curve the bowl's base spread the flux sufficiently. The

odd positioning of the lamp-holder at the roadside of the lantern can clearly be seen here. Also the silver

identification sticker – another requirement of by BS 1788:1964 – can also be seen.

|

|

|

|

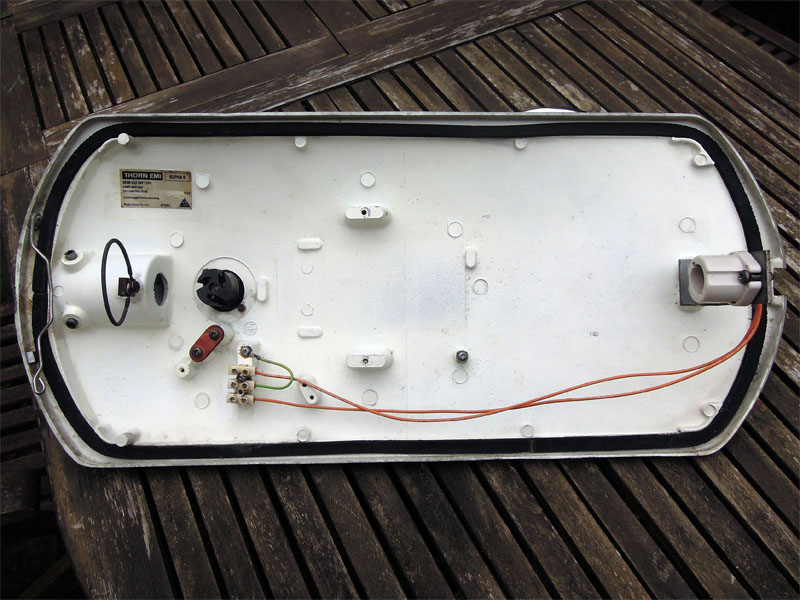

interior #1

The canopy of the lantern had several lugs and screw fixings for the following (from left-to-right): fixing grub

screws (positioned at an angle to the spigot),

photocell mounting point,

provision for a large cable clamp (to accommodate extra wiring for the photocell),

cable terminal block,

earthing point,

cable guide,

two lugs for mounting the optional gear tray, and the lamp-holder assembly.

The interior of the canopy was painted white to act as a secondary reflector.

|

|

|

|

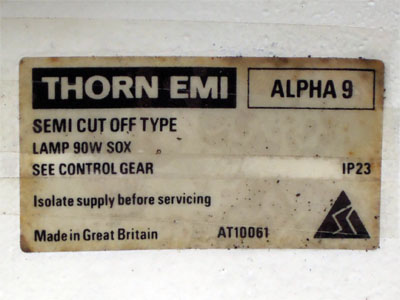

label

BS 1788:1964 required every lantern to have some form of identification. Many manufacturers used internal

stickers. The label included the following information:

Lantern's name: Thorn EMI Alpha 9

Optical system: Semi Cut Off Type

Lamp: 90W SOX

Ingress level: IP23

|

the thorn emi alpha 9 (qa9 d 1090) as aquired

Long Road cuts across the southern boundaries of Cambridge, the last direct

link between the fanning Hills Road and Trumpington Road. With its 1930s housing,

the road was probably populated as Cambridge’s suburban sprawl expanded during the

inter-war period. The street lighting was later, typical of the 1950s and 1960s

electrification schemes, and featured AEI Ambers on

REVO brackets and columns.

I was particularly interested in one lantern. At its midpoint, the road is raised

and travels over the Kings Cross and Liverpool Street railway lines. Along this

section, which was lit with Thorn Alpha Nines, was

a single lantern which was slightly different. The sides were black and the front

and back appeared louvered; whatever made this lantern odd was inside the bowl. If

Thorn ever designed a cut-off version of the Alpha Nine,

this is what it would look like. And there was a similar one near Cambridge Airport.

I often wondered if it was a very rare special; perhaps an experiment before

Thorn produced the Alpha Ten.

Recently relit to support a new cycle lane, the old SOX lanterns were replaced with

Philips Iridium lanterns on French style column and brackets

(think of a metal version of a Stanton 6B). My success

with Cambridge’s street lighting crews was zero at this point, but I had to try.

I spoke to the team taking out the old lights. Unfortunately my Alpha Nine

was still connected, and they expected it to be isolated at the end of the week.

As to the exact time, they didn’t know, but they said they’d cut the lantern off

and leave it in the bushes for me.

Yesterday, after returning from Dublin, I discovered my mysterious street light had

disappeared. And there in the undergrowth, as promised, was my lantern. So, many, many thanks

to that crew in Cambridge. And finally, I solved the mystery!

Yes - it's a standard Alpha Nine stuffed full of insulating tape. The louvering at

the ends was caused by the tape falling off the sides.

I think I'll keep it like this to remind me of my folly.

|