|

wardle liverpool

Genre: Enclosed Horizontal Traverse Low Pressure Sodium Lantern

The low pressure sodium discharge lamp was developed by Philips in 1932. After two successful trial installations

(including the first low pressure sodium installation in the UK along the Purley Way, Croydon) the first commercial installation

was installed by Liverpool Council in 1933 using specially commissioned lanterns from Wardle.

The development of lanterns continued through the 1930s and accelerated when it was determined that the lampís brightness and

its long length made it less susceptible to glare. Lanterns with bare bulbs suspended over an overhead reflector (the so-called "seagull" lanterns)

quickly followed. Glass manufacturers were initially slow as the first plate refractors for low pressure sodium lamps didnít appear

until the end of the decade.

The advantages and disadvantages of low pressure sodium were readily debated, especially when an alternative (the medium and high

pressure mercury discharge lamp) was also available. The monochromatic light was considered especially useful for arterial

and traffic routes, the lampís shape cast a wide beam across the road surface, the light was also considered more penetrating

in foggy conditions and it was the most efficient light source being manufactured. However, the light was also considered

inappropriate for high streets, promenades, civic areas and residential streets and so some lighting engineers

restricted its use to traffic routes only. Therefore low pressure sodium became known as "the driversí lamp."

The arrival of plate glass refractors resulted in large lanterns made of metal frames enclosing heavy glass sheets.

These bulky lanterns continued to be made into the 1950s until being usurped by lanterns with plastic bowls and

machined or moulded plastic refractor plates. The lanterns were still large; the size dictated by the bulky

control gear, but their design and construction was becoming simpler.

The 1950s and 1960s saw huge improvements in the construction and efficacy of low pressure sodium. Early two-piece

designs (dubbed SO) were replaced by the one-piece, more efficient integral design (called the SOI). The development of

linear sodium (SLI) broke the one hundred lumens per watt barrier, lead to a radical rewriting of the British Standards

of street lighting and prompted the development of new families of streamlined lanterns. But it wasnít until the arrival

of a new heat-reflecting technology (called SOX) that a cheap family of extremely efficient bulbs became available.

The energy crisis of the 1970s saw a rethink in street lighting and lamp efficiency became dominant when fuel was both

in short supply and expensive. This saw the large scale removal of colour corrected high pressure mercury, fluorescent and

ancient tungsten lamps by low pressure sodium replacements. The old arguments that the smoky-orange lamps were inappropriate

for residential areas no longer applied. By the end of the 1980s, low pressure sodium was the dominant street lighting lamp used in the UK.

The use of low pressure sodium came under scrutiny again. High pressure sodium, finally developed as a viable technology in the

1960s, was coming of age and offered a compromise of slightly less efficacy with better colour rendering. Questions were

being asked about the physiology of the eye and visual adaptation under low lighting levels; previously the wavelength

of low pressure sodium had been deemed the most suitable, but research now suggested that the eye responded better to white

light. Concerns were raised about light pollution and the low pressure sodium lamp was seen to be the chief culprit

(although it was more to do with older non-cutoff and semi-cutoff optical designs rather than the lamp itself).

By the turn of the century, the age of low pressure sodium was seen as coming to an end. Research in white light technologies,

especially metal halide and a renewed interest in compact fluorescent coupled with the advantages of using white light at

low lighting levels, saw the end of the low pressure sodium lampís dominance. Its use was discouraged in the specifications,

lantern manufacturers started to wind down their production and bulb manufacturers followed suit.

By the end of the first decade of the 2000s, low pressure sodium was in stark decline, and less and less of the UKís

streets were being lit by its characteristic orange glow.

Name: Wardle Liverpool

Date: 1934 - Early 1950s

Dimensions: Length: TBA, Width: TBA, Height: TBA

Light Distibution: Cut-Off (Pre Specifications)

Lamp: 140 SO/H

History

|

|

Faced with the modernisation of Liverpool's street lighting, the local lighting engineer P. J. Robinson elected

to use the newly introduced low-pressure sodium lamp. However, either no luminaires yet existed or none met his requirements.

So he took it upon himself to design a luminaire for the lamp in conjunction with Manchester based Wardle Engineering.

His luminaire was of classic frame construction with aluminium end-caps and canopy. The lamp, the newly introduced SO/H lamp,

was supported horizontally within the frame by both a lampholder (positioned inside an extrusion within the end-cap) and

a lamp-steady. No refractors yet existed so Robinson opted for a cut-off

distribution, with main beam focussing achieved by the use of two curved mirrors. (His choice of optical control

was probably also influenced by the trial Purley Way luminaires or the simpler European Philips SO-RA unit

which also had cut-off distributions). The first of Robinson's luminaires was installed on the streets of

Liverpool in 1934 and this is believed to be the first non-trial installation of low-pressure sodium in the UK. (Although

I've yet to find a reference for this). In honour of the city, and its lighting engineer, Wardle named the luminaire

the "Liverpool."

Contemporary lighting practice, in part following from work by Waldram in the late 1920s, suggested a central

mounting position for cut-off luminaries. This led to Robinson's Liverpool units being mounted on

incredibly ungainly columns with enormous outreach brackets that positioned the luminaire over the centre of the

carriageway. This poor aesthetic appeal was further exaggerated by external, high-level cabling and the addition of

squat, functional gear boxes bolted to the column. Yet his belief in low-pressure sodium was unfailing and Liverpool

became the first city to adopt this new lamp for all its major roads. Robinson's Liverpool luminaire

also became a popular seller for Wardle, who fondly recalled their earliest sodium luminaire in their

later advertisements.

The trend in the UK was towards non-cut-off and semi-cut-off optical systems, so the cut-off Liverpool only

found a niche use outside Liverpool. (This was further reinforced by the MOT Departmental Report of 1937 which advocated the

non-cut-off system). The manufacture of glass refractors for the lamp in 1936, and the post-war development of plastic

optical equipment, saw the lantern looking antiquated and niche by the early 1950s. It was eventually replaced by sleeker

and smaller cut-off designs.

|

Popularity

Despite ongoing orders from Liverpool, who continued installing the lantern into the 1950s, and the notable

1936 Purley Way scheme, the lantern saw little general use.

Identification

The lantern's opaque sides, curved interior mirrors, lampholder extrusions at either end and

top-entry assembly (with its small diameter connecting conduit) makes this an easy lantern to identify.

Optical System

The primary optical system comprised of two curved glass reflectors positioned either side of the lamp. The reflectors,

and the positioning of the lamp within the opaque lantern body, created a cut-off distribution. Four wing nuts, two on

either side of the lantern for each curved reflector, allowed the optical system to be adjusted for either a 20' or 25'

mounting height. (The MOT Departmental Report of 1937 finally resolved the mounting height issue, standardising it at

25').

Gear

The lantern was never equipped with gear.

the wardle liverpool in my collection

|

|

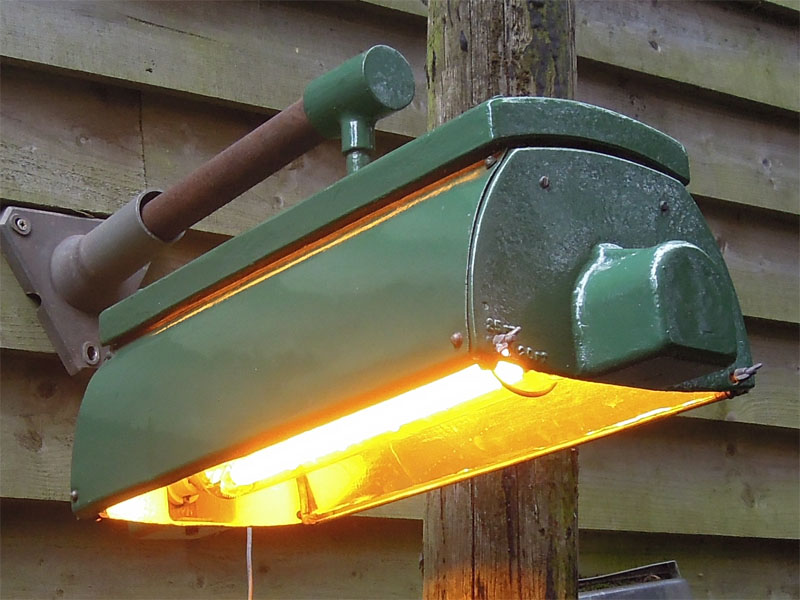

facing profile

This lantern was originally installed in the West Derby suburb of Liverpool. It was removed in the 2000s and acquired

by fellow collector Colin Jackson who gave it to me. After over 50 years of service, the lantern was in dreadful

condition and was little more than a shell.

|

|

|

|

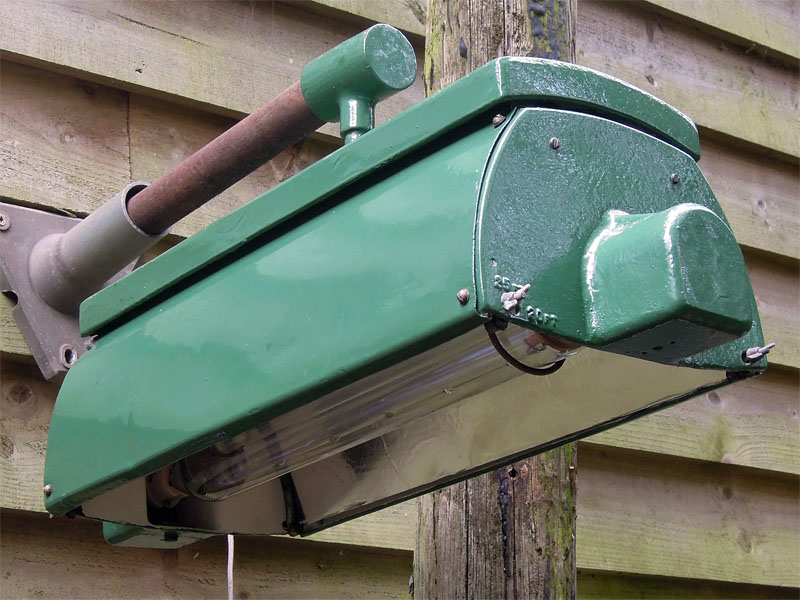

front profile

It has been fully restored and painted a dark green. In this shot, the two wing nuts which positioned

the mirrors for either 20í or 25í mounting height can clearly be seen.

|

|

|

|

trailing profile

The lantern had a substantial aluminium top canopy to which was bolted two frame end-pieces. Onto

these were screwed two identical end-caps Ė so both had lampholder extrusions although only one was

occupied Ė and the two opaque curved thin aluminium side pieces.

|

|

|

|

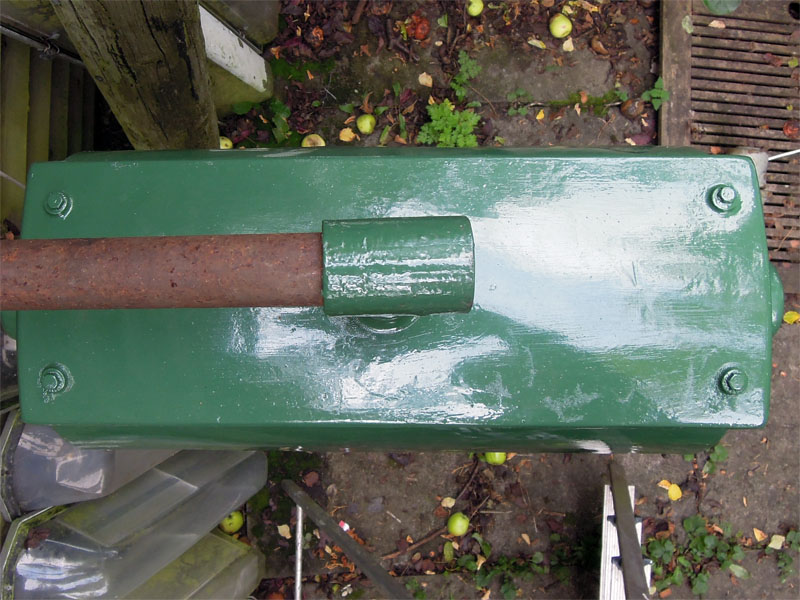

canopy

The two frame end-pieces were held in place by substantial bolts which screwed through the top of the canopy.

The mounting conduit had a tiny diameter and necessitated an adaptor T-piece to allow it to be screwed onto standard

diameter brackets.

|

|

|

|

logo

No logo or identification was found on the lantern. The top of the canopy was entirely smooth. However, they

were never there and had not corroded away, as various part numbers could be found on the components which made

up the lantern.

|

|

|

|

pedestrian view

The base of the lamp can just be seen in this shot. The mirrors were held in curved slotted brass mounts

that pivoted by a screw at the top and could be moved slightly by the wing nuts at either end of the lantern.

|

|

|

|

vertical

The whole interior of the lantern was painted white to act as a secondary optical system. The main beams

were fashioned by the curved mirrors which were positioned on either side of the lamp. The interior was

also extremely basic as there was just one mounting point for a terminal block.

|

|

|

|

gear box

One of the gear boxes was also rescued and this was completely restored. It contained a large leak transformer, square

condenser and two fuses. These were all extremely rusted and degraded. Therefore, the restoration here was just to

clean everything up, repaint the box and add a new sticker to the leak transformer.

|

the wardle liverpool as aquired

Two Liverpool lanterns and gear boxes were obtained from West Derby in Liverpool by Colin Jackson when

they were removed in the early 2000s. (He just missed the street lighting engineers and had to follow them to their

next job before rescuing the lanterns).

They had been painted grey and were in dreadful condition after being in service for 50 years. They were battered and

bent, there were holes in the side panels, the mirrors were long gone, the lamp steady was falling to pieces and all the

wiring was hard and brittle.

The best pieces from both lanterns and gear boxes were used to make a complete example. This was then restored.

|