|

the public lighting engineer at work

This article was originally published in: Public Lighting Vol. 2, No. 1, June 1936

© Institution of Lighting Engineers

Hover your mouse over the images to get a description.

An interview with Mr. Thomas Wilke, Public Lighting Engineer of Leicester

|

PUBLIC LIGHTING - like all important public services - is so common and so natural to the town dweller that

he seldom stops to ask the question: "How is this thing done?"

In this spirit of curiosity the writer set off to find a typical Lighting Engineer at work,

and to put the question in person; and so it was that one morning Mr. Thomas Wilkie, Public Lighting Engineer of

Leicester, received a visitor - one who was out to ask questions on the matter of street lighting, and to enquire

how this important municipal service is carried on.

* * *

"Good morning, Mr. Wilkie" ! In response, a very cheery faced Scot gives a cordial greeting putting his

caller at ease, and at once expressing a willingness to answer as many questions as possible if, in

so doing, he can be of service to Public Lighting Engineers in general.

"Good morning, Mr. Wilkie" ! In response, a very cheery faced Scot gives a cordial greeting putting his

caller at ease, and at once expressing a willingness to answer as many questions as possible if, in

so doing, he can be of service to Public Lighting Engineers in general.

"Mr. Wilkie, I understand that you are a Public Lighting Engineer pure and simple, and not necessarily

biased in the use of gas or electricity."

"That is so! As a Public Lighting Engineer I am primarily concerned in the matter of good lighting of streets

and highways, and to this end I am prepared to get the best possible results from whatsoever source of supply is available."

"Which do you prefer, gas or electricity?"

"My answer to that," said Mr. Wilkle, "is that in my area I have both gas and electricity, and I am content for my

committee to agree that I get the best results obtainable in each case. In fact," he continued, "my opinion

is that the function of the Public Lighting Engineer, when appointed by a Local Authority, should be to advise

in all matters of public lighting as a service, and to improve existing conditions rather than condemn one method

of supply in an endeavour to adopt another."

"My answer to that," said Mr. Wilkle, "is that in my area I have both gas and electricity, and I am content for my

committee to agree that I get the best results obtainable in each case. In fact," he continued, "my opinion

is that the function of the Public Lighting Engineer, when appointed by a Local Authority, should be to advise

in all matters of public lighting as a service, and to improve existing conditions rather than condemn one method

of supply in an endeavour to adopt another."

It was at once apparent that the Public Lighting Engineer of Leicester was keen upon his task-lighting,

and good lighting of the streets of his city was his business, and with the characteristics of a

Scotsman for thoroughness his work is well doneas this, story will show.

"You appear to have a big area to serve, Mr. Wilkie."

"Yes ! Leicester has a population of 262,000, and there are 8,954 gas and electric lamps to

illuminate its 260 odd miles of streets."

* * *

Twelve years ago Thomas Wilkie accepted the appointment as Chief Lighting Superintendent

(the City Council subsequently altering title of appointment to Lighting, Engineer) with the Leicester

Corporation, having gained his earlier experience in the Lighting Department of the Glasgow Corporation.

His appointment to Leicester was perhaps unique, inasmuch that Leicester was one of the first, if not the

first city in England to have a separate lighting department.

Its experience over the past twelve years should be of value to other municipalities.

In September, 1923, when he came to Leicester, Mr. Wilkie found his headquarters completely

inadequate for the eventual work of the department. The office existed only in name, and there

were neither furniture nor records. The premises were surrounded with old buildings occupied by

other tenants, and the yard was shared by them. The inadequacy of the headquarters was readily

admitted by the Lighting Committee, and immediate steps were taken to remedy it. The leases of

sub-tenants were determined, all the old buildings demolished, and new premises erected.

New headquarters were opened in July, 1927, and even those buildings have since outlived their usefulness,

for to-day much larger and far better equipped offices have been taken over.

* * *

"Tell me, Mr. Wilkie, do you find plenty of work for your men to do in the day as well as night?"

"Well, listen to these figures from my records.

"Last year the area of glassware cleaned in street lamps amounted to 262 acres!

"The number of miles walked by departmental employees amounted to 135,000 miles, which is equivalent

to five and a half times round the world!

"Over 11,000 miles of lighting were inspected after dark, that is, approximately 30 miles of lighting is inspected nightly.

"This particular night work is a continuous process which nothing is allowed to interrupt, and its

efficiency is shown by the fact that failure of lamps from all causes, controllable and otherwise,

is considerably less than 0.1% nightly."

"It appears to me, Mr. Wilkie, that the Public Lighting Engineer's appointment is no sinecure?"

"Oh, no ! But that which I have already told you is ordinary 'bread and butter work'; you have not

seen where we do much of the most important research work. Would you like to look round our laboratory?"

* * *

To the mere layman, many of the interesting instruments seen and demonstrated left him bewildered,

yet greatly impressed in the fact that present-day street lighting is no longer the old-time conception

of providing a series of points of light, but is an advanced science.

To the mere layman, many of the interesting instruments seen and demonstrated left him bewildered,

yet greatly impressed in the fact that present-day street lighting is no longer the old-time conception

of providing a series of points of light, but is an advanced science.

The laboratory has been designed with the same meticulous care and thought that marks

all the general details of the Leicester Lighting Department, and Mr. Wilkie has his

fingers on every point of his organisation.

The work carried on in this laboratory is perhaps the most important part of the duties of

the department, and among the normal routine is:

- Testing of fittings supplied on tender to ascertain if they fulfil the conditions laid down;

these conditions refer, to calculations relating to road width, mounting height of unit proposed,

and the spacing of units which it is found desirable to adopt.

- Subsequent further tests of fittings which have been in service to ascertain amount

of light depreciation and, where possible, devise means of reducing that depreciation.

- Fixing of focal position of electric fittings to ensure that main beam candle

power is obtained at the pre-selected angle.

- Deciding the periodicity of cleaning the various types of glassware in use, having regard,

again, to light depreciation caused by dust, elements, etc.

- Testing of electric lamp filaments to ascertain if normal life of 1,000 hours' burning

is maintained, and also if lumen output falls below the limit guaranteed.

- Testing of strength of gas mantles mechanically, both by "Durameter" and Shocking Machine.

- Similar tests on gas mantles and gas fittings as obtain with electric fittings as regards light depreciation.

- Re-calibration of gas burner nipples by means of Test Gas-Holder, which permits the actual mains pressures on

streets to be reproduced at will.

Like a small schoolboy the writer became still more curious-one never thought that Public Lighting meant

all this inside work. The plotting of those curious graphs, so much beloved by the engineer-the minute

examination of lamps and fittings-the re-examination of lamps taken from service to ascertain whether they

are maintaining their standard of brilliance, to say nothing of the complete life record of each lamp supplied

to the Corporation-and there were 5,348 electric filament lamps used last year !

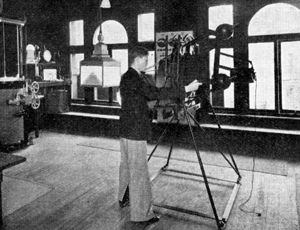

Test Laboratory

Space does not permit of a full catalogue of the contents of the laboratory, but the photometric section deserves mention.

Photometer Bench

This is a standard 12-foot bench, and is so arranged that it can be used in conjunction with either the Cube

or Radial Photometer.

The photometer head is of the Lunimer Brodhun contrast type, and ordinary gas-filled lamps are

used as sub-standards, calibrated from an N.P.L. standard.

Radial Photometer

The Radial Photometer or Polar Curve Apparatus is used for determining the candle-power of a

lantern in all directions. It consists of two mirrors capable of rotating in a vertical plane;

one of the mirrors describes a circle about the lantern, the light being reflected at each angle

on to the second mirror, and thence to a photo-electric cell. A 12-foot light path is given

between the lantern and the cell.

The cell is calibrated against a visual reading on the bench before each test, adjustment being obtained

by means of an iris diaphragm in front of the cell and a magnetic shunt in the field of the moving-coil

galvanometer on which readings are taken.

The lantern mounting is capable of mechanical rotation horizontally through 3600 in 50 steps,

thus enabling the complete distribution to be obtained in both vertical and horizontal planes.

Integrating Cube

The 7-foot integrating cube is used to measure the total luminous output of either a lamp or

lantern. It is painted internally with a flat white paint according to the British Standards

Institution Specification. The lamp (or lantern) to be tested is suspended in the centre by an

adjustable holder. In the centre of one side is a small glass window, behind which is a

photo-electrie cell connected to a galvanometer. There is also another window for use with the photometer bench.

The cube is calibrated from a standard lamp of known luminous output. The voltage at

the standard lamp is kept constant by regulating resistances, while the photo-electric

cell is adjusted until the galvanometer reads the output of the lamp. The cube is then calibrated.

Comparisons of the luminous. output of the lamps can easily be obtained by putting the

lamp in the cube, running it at its rated voltage, and reading the lumen output on the galvanometer.

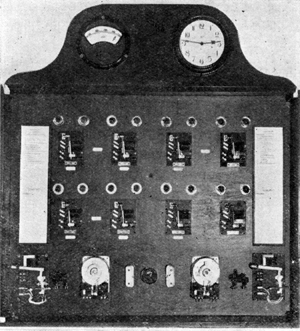

Main Road Control-Panel

Our attention is next drawn to a very simple and innocent-looking electric switchboard.

"From here I can control the lighting of two-fifths of the main roads of Leicester," said Mr. Wilkie.

"That doesn't sound possible with such small switches."

"Well, try for yourself."

And so we switched on the lights of Leicester - a definite thrill, and there on a "tell-tale" clock

was automatically recorded the fact that at 2.30 p.m. on a particular afternoon a full load was put on for 30 seconds.

"But how is it done, Mr. Wilkie?"

"Quite simple! It is intended that ultimately all main roads will come under this control."

"The roads are divided into four main sections, each controlled by an automatically wound and set time-switch,

and each consists of a number of relay circuits connected in cascade, the last lamp in each circuit

operating the relay for the next circuit. Pilot lamps, connected to the last lamp of each section,

indicate failure in any circuit, and a system of further pilots insures against the line being made

live while workmen are working on any line. Any circuit can be isolated from the rest of the section."

"The chief advantage of the system is that the whole of the lamps connected can be switched on instantly

in case of fog or sudden darkness."

"Up to the present there are 430 200w. to 500w. lamps controlled by this system."

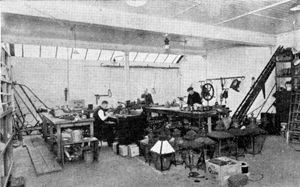

Workshops

A visit to the well-equipped workshops and stores was next made. Here repairs of all kinds

are carried out by an efficient staff.

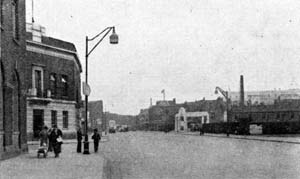

Before making our departure from Leicester Mr. Wilkie took us through many of the streets

in and around the city - and what a delightful city Leicester is - in order to see the different forms of lighting employed.

Before making our departure from Leicester Mr. Wilkie took us through many of the streets

in and around the city - and what a delightful city Leicester is - in order to see the different forms of lighting employed.

A camera recorded a few of the streets; typical examples are illustrated in these pages.

"One more item of interest is still to be seen," says our guide as he brings us to, a point where new

lamps are being fitted to existing tramway standards.

Before us is a familiar type of ladder in a new guise. "Surely it's an old fire escape!" Yes, and so it was, and

to what valuable purpose it was now being put!

It appears that the Fire Department was "scrapping" the escape for a newer model, when the keen

eyes of Leicester's Public Lighting Engineer saw in it the making of an ideal repair-work ladder for

overhead work. A little thinking, some sound reasoning to the Public Lighting Committee, a financial

sanction, and today Leicester possesses one of the neatest and handiest types of vehicle for the particular

work to which it is called. From the illustration it will be seen with what ease the men can work, and note

also how clear of the roadway stands the vehicle. The ladder and raising and lowering gear is mounted on a Bedford truck.

The department also possesses a similar ladder, but a little smaller, mounted on a Morris Commercial 30-cwt. chassis.

And so, as we left that city, situated as it is in the very centre of England, it was with a deeper

regard for him whom we can style as a typical Public Lighting Engineer, whose daily endeavour is

to brighten the highways after daylight has gone, and who surely lives by the motto: Post tenebras lux.

© Institution of Lighting Engineers

|