|

Street Lighting

by C. R. Bicknell, B.Sc, F.I.E.S

This article was originally published in: Public Lighting Vol. 10, No. 36, January-March 1945

© Institution of Lighting Engineers

This valuable contribution, supplied by the Engineering Department of Siemens Electric Lamps and Supplies,

Ltd., deals fully with modern standards for street fighting, and will provide useful information for engineers

contemplating new installations in the post-war period.

General

We are within sight of the time when normal street lighting will again be permissible, and the

attention of local authorities generally is now directed towards the restoration of this

very important peace-time amenity. Those authorities whose street lighting had been brought

up to modem standards, before the outbreak of war have, in the main, already taken the

steps necessary to condition it for the day when it may again be brought into use. Many others,

who had been considering plans for the re-lighting of their streets when war broke out are now

reviewing the situation with a view to proceeding with the installation of up-to-date system

as soon as practicable, but there still remain many many miles of streets sadly in need of

the attentions of the street lighting engineer.

In some areas where the public lighting is completely out of date, damage by enemy action will

necessitate the purchase and installation of new equipment, and here, surely, the opportunity

will be taken to make a clean sweep of the old, and replan the lighting as an integral part

of the post-war reconstruction effort. It is to be hoped, too, that similar action will be taken in other areas.

It is a reasonable assumption that every local authority has always had the wish to light its

streets properly, and has only been deterred from taking the steps necessary to implement this

desire by the costs involved. Because of this matter of expense there has been a tendency for some

councils to regard anything better than the irreducible minimum of street lighting as an

expensive luxury, instead of as an economic necessity, which is its real status.

A serious difficulty that at present stands in the way of the provision of a uniformly good standard

of street lighting lies in the fact that, with the single exception of scheduled trunk roads

referred to later, the whole cost of street lighting has to be borne by the local taxpayers.

In districts where the rateable value of the property is high, a penny rate will produce a very

large sum of money, and a comparatively small increase in the rates would find all the money

necessary to install and maintain a first-class system of street lighting. In other

districts an impossibly high rate would have to be imposed to provide the same standard.

No one, surely, will suggest that the ability or inability to meet the cost of adequate public

lighting affects the issue as to its necessity or otherwise, and it if is necessary in places

of high rateable value it is equally necessary in less well favoured localities.

In many instances, the outlook on street lighting is too parochial. Street lighting is not installed

for the exclusive benefit of those resident in a particular locality, but equally for the convenience

and safe conduct of the many who visit or pass through it, and it seems only reasonable that

the onus of its provision should be shared more equitably. Methods of spreading the cost of

street lighting over a wider area than is at present the case have been suggested, such as

that the cost be met in some degree from national funds and that the power to light roads be confined to

larger administrative units than at present. Whatever course is adopted, it certainly seems that some

change from the existing system merits consideration.

As has been indicated, roads scheduled in the Trunk Roads Act do receive special consideration by the

Minister of Transport, who is empowered to sanction payment by the Ministry of up to 50 per cent

of the approved cost of lighting installed on such roads and of the maintenance of such installations.

The Ecomonic Aspect

The writer has suggested that good street lighting is an economic necessity, and in support of this statement

adduces briefly the following facts.

In peace time, 38 per cent of the total fatal casualties on the roads occurred after dark. In the first

year of the war this figure rose to 54 per cent., and in the second war year was 43 per cent. In assessing

the significance of these figures full cognisance must be taken of the fact that with the war-time restrictions

imposed on the use of motor vehicles, the traffic on the roads, particularly at night time, had very

considerably declined from its peace-time level during the war years under consideration. We can,

therefore, draw the conclusion that the increases noted were due to the enforcenwnt of, black-out regulations - in

other words to insufficient lighting - and can infer that but for the reduction in traffic density the increase

in the number of night fatalities would have been still greater.

In the course of a debate in the House of Commons in 1936, it was revealed that the cost of road accidents

in one year in this country was 25 million pounds. This was the sum actually paid out by the insurance companies,

but money paid out by these companies has first to be paid in by the general public.

It is difficult to obtain statistics in this country from which to deduce the effect of improved street

lighting on the night accident rate, but the effect of reduced lighting has already been shown, and a

classic example on the other side can be seen in the Victoria Embankment. Here, the number of night accidents

involving vehicles was reduced, following the re-lighting of the thoroughfare, by 31 per cent. during the six summer months,

and by 81 per cent. during the six winter months.

Enough has been said to show that good street lighting does reduce night accidents, and it has been said with more

than a measure of truth, that the community pays for good street lighting whether or not it gets it. In other

words, the cost of the extra accidents due to indifferent street lighting is far greater than the cost of

improving the street lighting and, in the long run, it is the taxpayer who bears this cost in the form of

increased insurance rates, etc.

The Objects Of Street Lighting

The primary object of street lighting is to provide sufficient visibility to ensure, as far as possible, the

safety of the public and its property during the hours of darkness.

With the removal of war-time restrictions on the use of motor vehicles, a great and growing density

of traffic on the roads must be expected, and consequently the responsibility for ensuring its passage

with the least danger to itself and others will present a serious problem. Before the war long distance

night travel and road transport was on the increase, and the same trend must be looked for in the future.

History shows that great wars tend to be followed by crime waves, due in part to relaxation of the restraint

and discipline to which so many have been subjected. The average criminal lurks and works in obscurity, and

good lighting of our streets and enviromnents can act as a crime deterrent for raising the risk of detection to

an unprofitable extent for the would-be criminal.

Properly lighted, thoroughfares enable pedestrians to move about at night with the same confidence, comfort

and safety as by day, whilst shopping areas and important urban centres can be made additionally attractive

with consequent benefit to the shopkeeper and the locality.

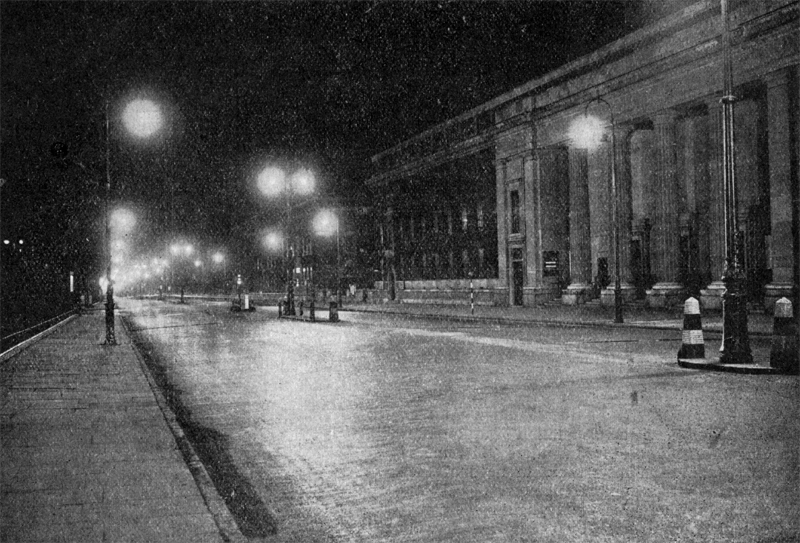

An example of Dual-Carriageway Lighting in the Euston Road, London, a Double-Staggered System being employed.

The complete visibility over road and footpath and clear definition of the kerb line will be noted. Sufficient

but not excessive light for aesthetic and police purposes falls on the buildings. The lighting is by 400 watt Sieray Lamps in

Regent Sieray-Lanterns.

Standards Of Good Street Lighting

The need for the establishment of standards of good street lighting and methods, to attain it

was recognised by the Minister of Transport in 1934 when he appointed a Departmental Committee "to examine and

report what steps could be taken for securing more efficient and uniform street lighting, with

particular reference to the convenience and safety of traffic and with due regard to,

the requiremerits of residential and shopping areas, and to make recommendations."

The findings of this Committee were published in

the form of an Interim Report in September, 1935,

and a Final Report in August, 1937. For the purposes of their deliberations, the Committee divided

roads into two classes, Traffic Routes (Group "A") and Other Roads (Group "B"), and the recommendatians

made in these reports were in line with good contemporary practice which was, itself, based on

technical research carried out by firms in the industry.

For some five years our thoughts and activities have been concentrated on matters other than

street lighting, and it may, therefore, be helpful to, review the salient points of the reports in question.

Before doing so, we would mention that there is a considerable school of thought that considers it would be

an advantage to classify roads into three or four groups, instead of confining the classification to two. This

matter of the further sub-division of roads for lighting purposes is not one to be discussed here; we have,

in the Departmental Report, specific recommendations which, if followed, will provide a good uniform standard

of street lighting, and it is unlikely that any good purpose would be served by discussing in this article matters

which, at this juncture, might only confuse the issue.

Recommendations for the Lighting of Traffic Routes (Group "A")

- Mounting Height to centre of light source: of the order of 25 ft.

- Spacing. Generally not greater than 150 ft., but under, special circumstances an occasional

span may be as much as 180 ft. maximum. Where economically practicable, a closer spacing, e.g., 120 ft. may be adopted with advantage.

- Overhang. Such that the maximum distance between the two. rows of light sources

does not exceed 30 ft. with a maximum overhang of 6 ft. If on account of the width of the road these

conditions cannot be satisfied, the sources should be mounted over the kerbs, and additional sources be sited

down the centre of the carriageway at intervals not exceeding three spans.

- Amount of Light. For a carriageway not more than 40 ft. in width, the luminous output of the

lantern, based on the average light output of the light source through life per 100 ft. linear of road should

exceed 3,000 lumens and lie between this figure and 8,ooo lumens. The additional light required for carriageways

exceeding 40 ft. in width will be provided by the centrally placed sources.

- Distribution of the Light. The available light should be employed to produce the maximum

contrast between the brightness of the object to be viewed and its background, subject to the avoidance of undue glare.

- Glare. The Committee expressed the view that with a non-axial distribution of the

light the ratio of the peak candle-power to the average of the values in all directions downward from the source

and lying between 30o and 45o from the vertical should not exceed 6, and preferably be not

greater than 5. With axial distribution the ratio should not exceed 5.

- Siting of Columns. Single side lighting should be avoided except on bends, and central

suspension, except where the carriageway is narrow, possesses many disadvantages with most of the types of

distribution in common use before the war, particularly if non cut-off fittings are used. With these provisos the

arrangement of the sources can be left to individual preference, but the advantages of the staggered

system are such that this form of lay-out is the one most generally used.

The above recommendations apply, in the main, to systems employing, lanterns of what may be termed the non cut-off type,

i.e., those in which the maximum intensities are directed at angles near to the horizontal. This type of distribution is

inevitably accompanied by'a certain amount of glare which, however, is not found to be intrusive if the requirements of

(vi) above are complied with.

MOUNTING HEIGHT AND SPACING. The mounting. height of 25 ft., and, generally speaking, spacing of 150 ft.,

giving a spacing/height ratio of 6 to 1, enable the lantern designer to produce a lantern that will illuminate the stretch

of road between adjacent columns to the desired intensity with a reasonable diversity factor and, provided the siting

is properly carried out, an absence of patches of shadow that would constitute danger areas. It might be supposed that

the area in the immediate vicinity of the light source would be free from dangerous shadows, but certain types of

lantern can be seen on otherwise well-lighted roads where even at quite short range it is possible for a

pedestrian in the vicinity of the column to be virtually invisible. The danger of this is obvious, and this fault

should be looked for when assessing the merits of different types of lanterns.

OVERHANG. The recommendation of a maximum overhang of 6 ft. is important, and is so included

because the absolute necessity of lighting the footpath adequately is recognised. Footpath lighting is necessary

to enable pedestrians to proceed on their lawful occasions in comfort and safety, but the amount of light and its

distribution that would enable them to do this would not necessarily be sufficient to enable the driver of a vehicle

to recognise the intention of such persons. It is essential for safety that the kerb line be well defined, and

that the lighting of the footpath be such that a driver can recognise the intention of a pedestrian, to cross

the road before he actually leaves the footpath.

Poor footpath lighting causes drivers, in self defence, to follow a course as far from the kerb line

as possible, thereby causing obstruction to faster moving vehicles and reducing the effective width of

the carriageway from a traffic carrying point of view.

Whilst it is agreed that good footpath lighting is essential, the lighting must not stop there, for it

is necessary that a certain amount be allowed to fall on to adjoining property, both from an aesthetic point

of view and to help, in safeguarding it from unauthorised encroachment. Most modern street-lighting

lanterns are so designed that sufficient fight is emitted on the pavement side to meet this requirement,

but it will be clear that the further a lantern is mounted beyond the kerb line the less effectively will

this particular function be performed.

AMOUNT OF LIGHT. A considerable variation in the amount of light to be allowed per 100 ft. linear

of road is permitted, and this is wise for it is a self-evident fact that the requirements of roads, even though

they may all be grouped into a single class, vary very widely. It is thus left to the local authority to

decide the relative importance of its roads from a lighting standpoint.

The Report recommends that the amount of light per 100 linear of road be between 3,000 and 8,ooo lumens, but it

should not be overlooked that this recommendation is made to cover the requirements of traffic routes, and

important central areas of large towns may need to be lighted to considerably higher standards than are covered by this range.

DISTRIBUTION OF THE LIGHT. It is the generally accepted view that objects on a road at night are

usually seen as dark objects against a light background, i.e., in silhouette. It follows, therefore, that

provided no disabling factor such as excessive glare is introduced by so doing, visibility will be increased

progressively the brighter the background and the lower the brightness of the object become. Now the

background against which most objects are viewed by a driver consists, in the main, of the road and pavement

surfaces, and consequently street lighting lanterns should be designed to produce, as high a surface brightness as

is consistent with tolerable glare. In order to achieve this end, optical systems are commonly designed to

direct light of high intensity at angles just below the horizontal, since road surfaces reflect light mainly

forward, and the more obliquely the light falls on to the surface the better will be the forward reflection.

We have referred specifically to the road, and footpath surfaces as backgrounds, but it is obvious that in our

efforts to obtain a high brightness contrast and good silhouette we must not overlook the part that can be played

by light coloured fences, walls, etc. These latter make a very valuable contribitti6n to visibility provided that

light from the street lighting units is allowed to fall on to and be reflected by them, and they are particularly

helpful at such places as road junctions and on bends.

Certain types of fittings are designed to project their highest intensities at angles substantially below

the horizontal, but these types, whilst reducing glare, are productive of a lower surface brightness and

consequently of a reduction in contrast 'between the object and its background. In the extreme case of this type

of fitting - the cut-off type - glare is eliminated entirely at all normal angles of sight but surface brightness

is, of course, still further reduced. With these types of fittings it is usually desirable to reduce the spacing to

a figure substantially lower than the 150 ft. recommended for the non cut-off type.

GLARE. As we have stated, a certain amount of glare is inseparable from street lighting systems of

the non cut-off type, but provided the directional intensity ratio laid down in (vi) is not exceeded, it is not, in practice, found

to cause disability to the road user.

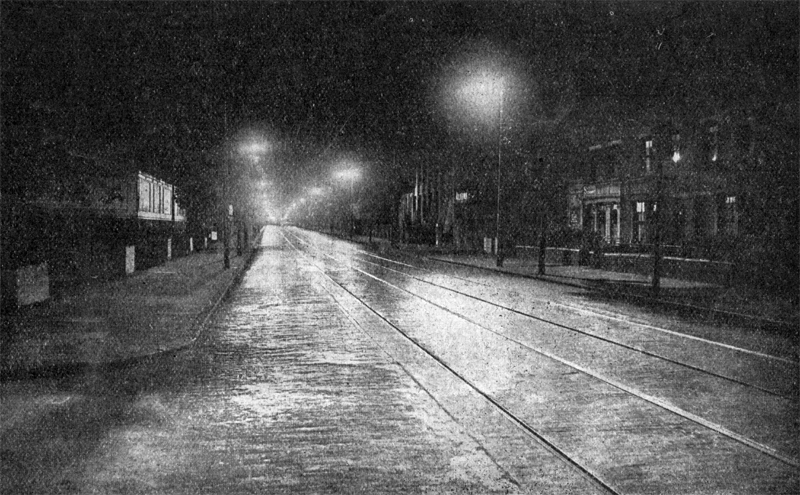

A Staggered System of lighting by 400 watt Sieray Lamps in Bi-way Lanterns at East Ham, London,

showing the clear visibility obtained by a driver over the carriageway and footpath. The usefulness of

the hoarding on the left in providing a bright background for traffic emerging from the side road on the

right will be noted. Although the road is tree bordered only the tree in the right foreground casts a

troublesome shadow which could be and was removed by lopping.

The Lighting of Other Roads (Group "B")

In this group the Departmental Committee has included all those roads that require street lighting but which do

not fall within the category of traffic routes. Owing to the wide variations that exist in the characteristics

of this class of road, general guidance rather than specific recommendations is given for their lighting.

It is, however, recommended that, in order to preserve a clear, readily recognisable differentiation between

roads in this group and traffic routes, the maximum height and maximum light output, as set out, be not exceeded.

In general, the essential requirements which should be met by the lighting of roads in this group are similar

to those called for from traffic route lighting. It is clear, however, that the lower mounting height does not

permit the projection of lighting units beyond the kerb line, and this introduces difficulties where tree-bordered

roads are concerned; in such cases every effort should be made by siting, tree loping, etc., to avoid the casting of

heavy shadows along the kerb line or across the road.

The lower limit of mounting height is dictated by the needs of achieving a satisfactory distribution

and the avoidance of undue glare.

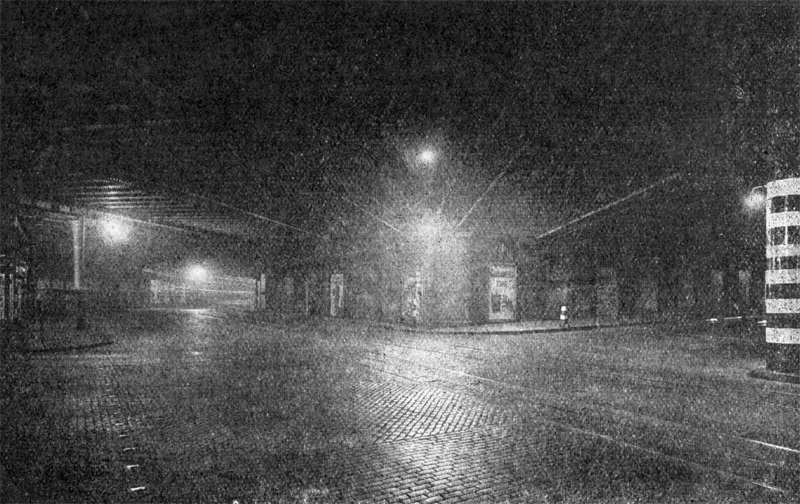

At the railway viaducts outside St. Pancras Railway Station, London, columns were sited, as far as possible, in gaps between

bridges to obtain the maximum mounting height. 250 watt Sieray lamps were used in lanterns with a symmetrical light

distribution to take full advantage of the backgrounds offered by the posters, and diffusing glassware limits the

glare that might otherwise obtrude owing to the lower mounting height.

Recommendations for the Lighting of Group "B" Roads

- Mounting Height. Between the limits of 13 ft. and 15 ft., preferably the top of this range.

- Spacing. Average not greater than 120 ft. with a maximum of 150 ft. for any one span in exceptional cases.

Where economically practical, a closer-spacing, e.g., 100 ft. should be adopted.

- Amount of Light. The luminous output of the lanterns, based on the average light output of

the light source through life, should be between 6oo lumens and 2,5oo lumens per 100 ft. linear of road.

- Distribution of the Light. Basically, the distribution of the light should be in accordance with

the same principles as those set out for traffic route lighting. Owing to the lower mounting height, however, it

may be necessary to pay rather more attention to ensuring that sufficient light is directed on to adjoining property

to meet police requirements.

- Glare. For non-axial fittings at an average spacing not exceeding 120 ft., the ratio defined in (vi) under

Lighting of Traffic Routes, should not exceed 4, and preferably be not greater than 3.

With axial distribution the figure should not exceed 3.

- Siting of Columns. A staggered system is recommended and the same principles as those set out for

the lighting of traffic routes should be applied. Particular care should be taken to meet the requirements

of junctions and intersections, at the expense, if necessary, of uniform spacing.

The Technique of Street Lighting

Street lighting technique, as applied by the street lighting engineer, consists in obtaining optimum

visibility for a given consumption of electrical energy and with reasonable installation and maintenance costs.

It will be noted that we have advisedly not said "with minimum installation costs," as factors other than

the primary cost should be considered when making a decision as to what particular equipment to purchase

and how to erect it. For example, local conditions may influence a decision as to whether the extra cost

of installing raising and lowering gear will offset the additional costs of maintenance by tower wagon,

and if the latter is decided on, whether it shall be of the man handling or motor driven type. Let us

examine the advantages and disadvantages of these two methods of maintenance:

Raising and Lowering Gear

- (i) Low labour costs for maintenance - a single man can change a lamp or clean a lantern.

- (ii) Lanterns are obviously more easily cleaned on the ground than at the top of a tower wagon.

- (iii) Unless the overhang is excessive, the maintenance can be effected without causing obstruction

to traffic on the road.

- (iv) Elimination of that risk of accidents to maintenance personnel which must exist where tower wagons are used.

- (v) Against these advantages must be set the increased cost of the installation and the additional equipment to maintain.

The Tower Wagon.

- (i) The cost of the necessary number of tower wagons will be less than the cost of raising and lowering gear.

- (ii) On the other hand, tower wagons must obstruct the road, to an extent that may be serious on narrow roads.

- (iii) With tower wagon maintenance, lamps are subjected to less shock than when the complete unit is lowered to

the ground for cleaning. There is always a tendency for jarring to occur with raising and lowering gear and this may

cause lamp filament fracture. Whilst this is not a serious risk, it exists, and should therefore rightly be mentioned

in assessing the merits and demerits of the two methods under discussion.

Again. two lanterns may give precisely the same light distribution; they may, in fact, employ the same

optical system, and lantern (a) may cost '25 per cent. more than lantern (b). If. however, the former is the more

easily cleaned and is made from materials that do not deteriorate with exposure to atmospheric conditions, whilst the latter

needs regular painting to prevent corrosion and can be expected to give a shorter life in service, it may be

sound economy to purchase the more expensive article.

Similarly, street lighting columns are commonly made from steel, cast-iron or ferro-concrete. Cost of the three types

differ, but each has its merits for any installation, whilst for use under particular atmospheric conditions one or

another may possess outstanding qualities. Space does not permit a discussion of the respective merits of these three

types of material for the manufacture of street lighting columns, but the lighting engineer must know their points

and thus be in a position to offer sound advice to the street lighting authorities to the most suitable -

which may not be the cheapest type to purchase for his particular local conditions.

Methods of control must receive careful consideration. These may take the form of:

- (a) Hand or time-clock operated circuit switches.

- (b) Individual time switches..

- (c) Centralised control of the high frequency impulse or D.C. bias type.

- (d) Contactors in cascade.

Having decided what materials to use and how much light a particular road is to have, the installation

must then be planned, and as regards the general principles on which a street lighting installation should

be designed there is little divergence of opinion amongst trained street lighting engineers. Technical

considerations and years of practical experience have shewn how to produce the best results with the tools

at the disposal of the lighting engineer, and the salient points of good street lighting practice may be

briefly summarised as follows:

- (i) Each lighting unit produces by reflection a patch of brightness on the road surface, and consequently

the units must be so sited that these bright patches fit together, like the pieces of a jig-saw puzzle, to

form a continuous bright ribbon.

- (ii) In order to obtain this substantially uniform brightness it is necessary that the road surface ahead of

the driver lie between him and the lighting units on his normal line of sight. From this it follows that a bend

must be lighted by points sited on the outside of the curve, and care must be taken so to regulate the spacing as

to avoid the appearance of dark patches on the surface.

- (iii) Special circumstances may necessitate the introduction of an occasional point on the inside of a

bend, but these should be additional to and not in substitution of those on the outside.

- (iv) Special care must be taken at road junctions and intersections and at traffic roundabouts to indicate

to traffic the existence of these points, to provide suitable and adequate background brightness to show up

any obstruction and to indicate the correct route through or round them. The basic principles necessary

to apply in order to, achieve these ends are indicated in the M.O.T. Report, but each case must be treated on

its merits.

- (v) Particular circumstances, such as overhanging trees, may call for special treatment and a departure from

the practice that one would. like to follow, but here, again, experience will produce a

reasonable solution.

- (vi) Care should be taken to ensure adequate lighting of kerbs, footways and, as already indicated,

adjacent property.

- (vii) Circumstances may justify the provision of an artificial coloured background upon which a sufficient amount

of light could be directed to improve visibility at awkward points. Such artificial backgrounds may well reduce

considerably the number of points necessary for the efficient lighting of bends.

Post-War Cooperation

We may expect that the cessation of hostilities will see the inauguration of an era of closer co-operation

between those bodies whose interests are allied to or run parallel with one another. This is a matter of

real importance in the field of public lighting if we are to attain the uniform level of good street lighting

throughout the country that is so desirable.

Before the war there appeared to, be growing a tendency for adjacent local authorities to consult together

before embarking on new street lighting projects, and nothing but good can come from such collaboration, for without it,

uniformity is impossible unless reached fortuitously.

We shall also hope to see closer co-operation

between those responsible for the planning and

maintenance of our roads and those whose duty it is

to light them, and having regard to the interest in

and knowledge of the fundamentals of street lighting that was being displayed in the immediate pre-war

years this hope is likely to be fulfilled. Without

it, the work of the street lighting engineer is not

only made more difficult - a point of little significance in itself - but is nearly always made more

costly. Street lighting installations can be planned

to provide any standard of illumination desired, no

matter what course a road may follow or of what

materials it may be constructed, but ill-planned bends need more points than gentle curves,

and there is a vast difference in the reflection factors of different road surfaces.

This matter of road surfaces presents a difficult

problem, since the highways and lighting authorities

demand such different properties from a surface,

and their several requirements are seldom exactly

met by any one type of surface. The highways

engineer is concerned with providing a surface that

will be durable and possess non-skid properties,

whilst the lighting asks for one that will give

effective diffuse reflection of light and thus provide

the high and even level of surface brightness necessary to give good visibility. If instead of reflecting

light efficiently, the road surface absorbs a large

proportion of it, more light must be provided at the

sources with consequent increase of cost.

In this connection, Dr. Merry Cohu carried out tests on actual sections

of road surfaces removed for the purpose from Paris roads, and found that if the

candle-power of a light source necessary to light a compressed asphalt road to a

given brightness is represented by the figure 1, the comparable figures for

wood block and bitumen surfaces are represented by 5 and 2.7 respectively.

In the words of the Departmental Committee's Report, "the road engineer can aid the lighting engineer

by employing light coloured materials for surfacing, and by avoiding as far as may be practicable the

use on the one hand of materials which produce a very dark matt surface and on the other of materials

giving a surface which is highly polished or which may become so under traffic."

Again, it is essential that the boundaries of a carriage-way be well defined and the provision of

light coloured kerbs by the road engineer helps the lighting engineer materially to achieve this by night.

An example of bad street lighting that has since been replaced with correctly sited modern equipment. Particular

attention is drawn to the bad condition of the kerb line and the absence of light on the right-hand footpath. There is an

almost undiscernible turning betow the arrow sign on the right of the photograph.

Judging A Street Lighting Installation

It might be felt that judging the merits of a street lighting installation is a matter well within the compass of any lay mind,

and that all one has to look for is the results achieved. In essence this is perfectly true, but there are pitfalls even here

for the unwary which may lead to false conclusions.

Prior to the outbreak of war a tendency was noted

in certain quarters to quote what was, in effect, the

efficiency of a lantern as a means of comparing one

unit with another. Nothing could be more misleading, sifice lantern efficiency by itself gives no indication

whatever that the light is being directed to

where it is required. If the argument were accepted

that such a figure serves any useful purpose at all,

we should have to admit that a bare lamp, which of

course emits 100 per cent. of its light, would provide

the best means of lighting a street, and we do not

think anyone needs convincing that this is absurd.

Similarly, lanterns should not be compared, except for appearance, by looking at them. The brightness of a

lantern is no indication of its efficiency as a street lighting unit.

If actual installations are being compared, they should be inspected under varying weather conditions.

An installation that may appear, and indeed be, first class on a fine night with a dry road, may be very

mediocre when it is wet. Similarly, a few points erected on a picked stretch of road do not necessarily indicate that

they are suitable for use where the conditions are not so favourable.

Installations should be viewed under normal traffic conditions, not when the road is free of traffic,

or a false impression may be received.

Finally, care should be taken to inspect street lighting installations from the viewpoint of a driver

preferably from a car in motion - otherwise there is no assurance that the driver is

given full visibility, e.g., over footpaths.

Maintenance

However high in quality an article or piece of apparatus may be, it cannot continue to function satisfactorily

unless it is maintained efficiently. Street lighting equipment is, generally, designed and manufactured so that

it can be kept in a state of mechanical and optical efficiency with the minimum of attention, but that

necessary attention must be given to it.

Street lighting lanterns are exposed throughout their useful lives to very varying conditions of temperature and weather,

and although the use of noncorroding metals, smooth exterior surfaces of refractors, total enclosure of lanterns, etc., lengthen

the period between the necessary attendances of the maintenance personnel, a regular maintenance programme is

essential.

It is not practicable, even for any specific type of equipment, to suggest how often lanterns, etc.,

should be cleaned, since this depends so largely on local conditions. Obviously, a smoky atmosphere or one

that is on occasions salt laden will call for more frequent work by the maintenance staff than would be necessary

in a country town.

Modern electric lamps have a very long life before mechanical failure occurs and are, we are afraid, far too

often kept in service long after their efficiency has fallen to a figure that makes their continued use an

uneconomic proposition. A proper maintenance programme will take cognisance of this fact and cater for

the replacement of lamps as necessary to maintain the whole installation a high level of efficiency.

Conclusion

To sum, up, the principal points of a successful street lighting installation are:

- (i) The equipment should be chosen for its suitability, durability, ease of operation and maintenance, and lastly price.

- (ii) The planning must be carried out by personnel well versed in the technique and practice of street lighting.

- (iii) An adequate maintenance programme must be drawn up and adhered to.

|