|

gec Z9536m

Genre: Enclosed Horizontal Traverse Low Pressure Sodium Lantern

The low pressure sodium discharge lamp was developed by Philips in 1932. After two successful trial installations

(including the first low pressure sodium installation in the UK along the Purley Way, Croydon) the first commercial installation

was installed by Liverpool Council in 1933 using specially commissioned lanterns from Wardle.

The development of lanterns continued through the 1930s and accelerated when it was determined that the lampís brightness and

its long length made it less susceptible to glare. Lanterns with bare bulbs suspended over an overhead reflector (the so-called "seagull" lanterns)

quickly followed. Glass manufacturers were initially slow as the first plate refractors for low pressure sodium lamps didnít appear

until the end of the decade.

The advantages and disadvantages of low pressure sodium were readily debated, especially when an alternative (the medium and high

pressure mercury discharge lamp) was also available. The monochromatic light was considered especially useful for arterial

and traffic routes, the lampís shape cast a wide beam across the road surface, the light was also considered more penetrating

in foggy conditions and it was the most efficient light source being manufactured. However, the light was also considered

inappropriate for high streets, promenades, civic areas and residential streets and so some lighting engineers

restricted its use to traffic routes only. Therefore low pressure sodium became known as "the driversí lamp."

The arrival of plate glass refractors resulted in large lanterns made of metal frames enclosing heavy glass sheets.

These bulky lanterns continued to be made into the 1950s until being usurped by lanterns with plastic bowls and

machined or moulded plastic refractor plates. The lanterns were still large; the size dictated by the bulky

control gear, but their design and construction was becoming simpler.

The 1950s and 1960s saw huge improvements in the construction and efficacy of low pressure sodium. Early two-piece

designs (dubbed SO) were replaced by the one-piece, more efficient integral design (called the SOI). The development of

linear sodium (SLI) broke the one hundred lumens per watt barrier, lead to a radical rewriting of the British Standards

of street lighting and prompted the development of new families of streamlined lanterns. But it wasnít until the arrival

of a new heat-reflecting technology (called SOX) that a cheap family of extremely efficient bulbs became available.

The energy crisis of the 1970s saw a rethink in street lighting and lamp efficiency became dominant when fuel was both

in short supply and expensive. This saw the large scale removal of colour corrected high pressure mercury, fluorescent and

ancient tungsten lamps by low pressure sodium replacements. The old arguments that the smoky-orange lamps were inappropriate

for residential areas no longer applied. By the end of the 1980s, low pressure sodium was the dominant street lighting lamp used in the UK.

The use of low pressure sodium came under scrutiny again. High pressure sodium, finally developed as a viable technology in the

1960s, was coming of age and offered a compromise of slightly less efficacy with better colour rendering. Questions were

being asked about the physiology of the eye and visual adaptation under low lighting levels; previously the wavelength

of low pressure sodium had been deemed the most suitable, but research now suggested that the eye responded better to white

light. Concerns were raised about light pollution and the low pressure sodium lamp was seen to be the chief culprit

(although it was more to do with older non-cutoff and semi-cutoff optical designs rather than the lamp itself).

By the turn of the century, the age of low pressure sodium was seen as coming to an end. Research in white light technologies,

especially metal halide and a renewed interest in compact fluorescent coupled with the advantages of using white light at

low lighting levels, saw the end of the low pressure sodium lampís dominance. Its use was discouraged in the specifications,

lantern manufacturers started to wind down their production and bulb manufacturers followed suit.

By the end of the first decade of the 2000s, low pressure sodium was in stark decline, and less and less of the UKís

streets were being lit by its characteristic orange glow.

Name: GEC Z9536M

Date: Late 1960s - Late 1980s

Dimensions: Length: 546mm, Width: 190mm, Height: 182mm

Light Distibution: Semi Cut-Off (BS 4533:1976)

Lamp: 35-55W SOX

History

The GEC Z9530 family of lanterns was introduced in the late 1960s. It was a complete

redesign of the firm's low-pressure sodium (LPS) lighting for side roads and was intended for side

road lighting, industrial roadways and/or general security lighting.

It replaced the earlier Z9480 range, which dated back to the early 1950s and was

now showing its age. The boxy squat profile, designed around the huge leak transformers of

the time, was over-sized and over-engineered, and could only accept the lowest wattage LPS lamps.

Therefore the Z9530 family was introduced as its replacement. Two main different sizes of

lantern were developed: a compact version which could only accept the 35W SOX lamp, and a

longer version which was designed for the 55W SOX lamp. The overall profile of the lantern

was also made smaller, now developed around the smaller gear options now available.

The lanterns initially conformed to the new British Standard Code of Practice for

street lighting: BS CP 1004:1963.

During the 1970s, new versions of the lantern appeared with Glass Reinforced Plastic (GRP) canopies.

These lightweight options were only available as a side entry option.

It remained a mainstay in the firm's portfolio, and its last lantern designed for both the smaller

SOX lamps. When the lighting department was sold to Siemens, and then to Whitecroft, the

lantern remained on catalogue, and could still be purchased into the 2000s.

Popularity

This family of lanterns installed in huge numbers and vied with the Thorn Beta 5 series and

Philips MI 26/36 as the most popular side-road lanterns in the UK.

Identification

The lantern was easily identified by the profile of its canopy, its narrow 'V' shaped bowl, its

distinctive small refractor panels, and the optional white over-reflector which

could be seen through the bowl.

The plastic bowls were often made of polycarbonate which was non UV-stabilized and so turned yellow over time.

Optical System

The primary optical system comprised of two plate refractors positioned either side of the lamp. As

the low-pressure sodium lantern already casts a wide beam in azimuth, the horizontal refractors simply

altered the flux elevation by fashioning two main beams in a semi-cut-off distribution

(in accordance with BS CP 1004:1963 and BS 4533:1976).

An optional over-reflector was available, used to cover the gear and provide a secondary optical system.

The exterior of the bowl was smooth to facilitate easy cleaning.

Gear

Optional gear was available and was mounted into the canopy of the lantern. This could be hidden by a stainless

steel over-reflector which was painted white.

the gec Z9536m in my collection

|

|

facing profile

Unfortunately I didn't keep a record of who I obtained this lantern from. Therefore its provenance is unknown.

However, it's very typical of this extremely common lantern.

|

|

|

|

front profile

The lantern was in good condition and only required minimal cleaning. The GRP canopy was covered in lichen, dirt and

moss which usually happens with this type of material.

The bowl had started to crack around the rivets holding the hinge assembly. This was due to corrosion and rust forming

on the rivets, expanding them, and causing the bowl to crack. This is a repeating problem with GEC bowls.

|

|

|

|

trailing profile

There was no photocell fitted. The hole was plugged with a tiny, plastic blank.

|

|

|

|

canopy

The bowl, whilst complete, wasn't in good condition. The polycarbonate had started to turn yellow after prolonged exposure

to sunlight.

|

|

|

|

logo

Like most GEC lanterns, the maker's logo was pressed into the canopy. The lantern would've also had an

identification sticker in the interior, but this had disappered during its many years of service.

|

|

|

|

pedestrian view

The bowl had a narrow 'V' shape, a profile used by the GEC for many years for their main road lanterns.

The refractors were molded into the angled sides, forming the two main beams. The base, being relatively narrow,

required no frosting or obscuring as the shape of the bowl helped to diffuse the light below the lantern.

|

|

|

|

vertical

This version of the lantern was extremely minimal and no over-reflector was fitted. The refractor plates didn't

extend over the lamp-holder assembly so that could be seen through the bowl.

|

|

|

|

open bowl

The spring latch holding the bowl closed was mounted at the pavement side of the lantern. This was to ensure

that the bowl swung outwards towards the road when opened. This prevented the bowl smashing agains the column if

it was mounted the other way around. The spring latch was extremely simple and allowed speedy opening and closing

of the bowl for service.

|

|

|

|

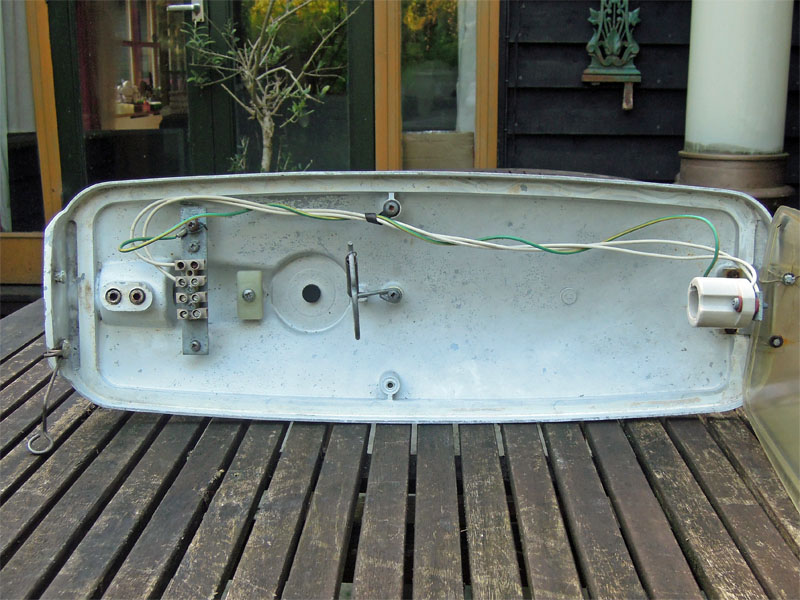

interior #1

The exterior of the lantern was extremely simple and simply featured (from left to right): bowl hinge,

bracket-mounting grub screws, terminal strip assembly (which could've been a later addition replacing the normal

live/neutral terminal block and earthing screw), cable clamp (for incoming cable), lamp steady and lampholder

assembly. The optional over-reflector was fitted using the central screws which explains why one of them is

earthed.

|

the gec Z9536m as aquired

A very popular lantern, this is the 55W version of GECs, and then Siemens

and then Whitecrofts range.

It's in an extremely grotty condition but should brush up OK.

|