|

Phosco P178

Genre: Post Top Lantern

The low pressure sodium discharge lamp was developed by Philips in 1932. After two successful trial installations

(including the first low pressure sodium installation in the UK along the Purley Way, Croydon) the first commercial installation

was installed by Liverpool Council in 1933 using specially commissioned lanterns from Wardle.

The development of lanterns continued through the 1930s and accelerated when it was determined that the lampís brightness and

its long length made it less susceptible to glare. Lanterns with bare bulbs suspended over an overhead reflector (the so-called "seagull" lanterns)

quickly followed. Glass manufacturers were initially slow as the first plate refractors for low pressure sodium lamps didnít appear

until the end of the decade.

The advantages and disadvantages of low pressure sodium were readily debated, especially when an alternative (the medium and high

pressure mercury discharge lamp) was also available. The monochromatic light was considered especially useful for arterial

and traffic routes, the lampís shape cast a wide beam across the road surface, the light was also considered more penetrating

in foggy conditions and it was the most efficient light source being manufactured. However, the light was also considered

inappropriate for high streets, promenades, civic areas and residential streets and so some lighting engineers

restricted its use to traffic routes only. Therefore low pressure sodium became known as "the driversí lamp."

The arrival of plate glass refractors resulted in large lanterns made of metal frames enclosing heavy glass sheets.

These bulky lanterns continued to be made into the 1950s until being usurped by lanterns with plastic bowls and

machined or moulded plastic refractor plates. The lanterns were still large; the size dictated by the bulky

control gear, but their design and construction was becoming simpler.

The 1950s and 1960s saw huge improvements in the construction and efficacy of low pressure sodium. Early two-piece

designs (dubbed SO) were replaced by the one-piece, more efficient integral design (called the SOI). The development of

linear sodium (SLI) broke the one hundred lumens per watt barrier, lead to a radical rewriting of the British Standards

of street lighting and prompted the development of new families of streamlined lanterns. But it wasnít until the arrival

of a new heat-reflecting technology (called SOX) that a cheap family of extremely efficient bulbs became available.

The energy crisis of the 1970s saw a rethink in street lighting and lamp efficiency became dominant when fuel was both

in short supply and expensive. This saw the large scale removal of colour corrected high pressure mercury, fluorescent and

ancient tungsten lamps by low pressure sodium replacements. The old arguments that the smoky-orange lamps were inappropriate

for residential areas no longer applied. By the end of the 1980s, low pressure sodium was the dominant street lighting lamp used in the UK.

The use of low pressure sodium came under scrutiny again. High pressure sodium, finally developed as a viable technology in the

1960s, was coming of age and offered a compromise of slightly less efficacy with better colour rendering. Questions were

being asked about the physiology of the eye and visual adaptation under low lighting levels; previously the wavelength

of low pressure sodium had been deemed the most suitable, but research now suggested that the eye responded better to white

light. Concerns were raised about light pollution and the low pressure sodium lamp was seen to be the chief culprit

(although it was more to do with older non-cutoff and semi-cutoff optical designs rather than the lamp itself).

By the turn of the century, the age of low pressure sodium was seen as coming to an end. Research in white light technologies,

especially metal halide and a renewed interest in compact fluorescent coupled with the advantages of using white light at

low lighting levels, saw the end of the low pressure sodium lampís dominance. Its use was discouraged in the specifications,

lantern manufacturers started to wind down their production and bulb manufacturers followed suit.

By the end of the first decade of the 2000s, low pressure sodium was in stark decline, and less and less of the UKís

streets were being lit by its characteristic orange glow.

Name: Phosco P178

Date: Late 1960s - Early 2000s

Dimensions: Diameter: 20", Height: 14½", Spigot: 3" dia. x 3" high

Light Distibution: None

Lamp: 35W SOX

History

|

Phosware (later CU Phosco) rode the wave of the post-war rebuilding boom, the company being

formed in the early 1950s to supply much-needed street lighting equipment. Although they initially supplied

a wide range of lantern types for many classes of lighting requirements, the firm always had a number of

different post-top designs on catalogue, catering for standard road lighting through to more decorative

examples for more environmentally sensitive areas.

Their earlier post-top lanterns were typically tall and elongated; a requirement of the vertically mounted lamp,

especially in the case of fluorescent tubes, where several 2-foot tubes needed to be accommodated.

In the late 1960s, the firm unveiled the P 178 post-top lantern which broke these design rules. Designed by

John Ricks, M.S.I.A., the P 178 was designed around a horizontally mounted lamp, in particular its

dimensions being dictated by the dimensions of the 55W SOX lamp (which was the largest it could accept). With its

wide tapered and vertical one-piece diffusing bowl, and its matching black spigot and hood, the lantern had an

unrivalled modern elegance, which was recognised by it winning a diploma in the Council of Industrial Design

competition.

Another, less popular, version offered some light control, combining a glass prismatic refractor dome with a 'pin-spot'

Perspex bowl. These could be used for the more efficient lighting of roads. This version of the lantern would've required

the lamp to be mounted vertically so the dome refractor could be fitted correctly.

The lantern was incredibly popular being used to light modern housing estates, industrial areas, car parks and

shopping centres. Its heyday was undoubtably the 1970s and 1980s and it could be found in almost every town and

city in the UK.

|

Popularity

The P 178 was extremely popular throughout the country. I'm sure almost every town and city in the UK

had an installation of them somewhere.

Identification

The lantern is easily identified by its dimensions (its wide width as opposed to height for post-top lanterns),

one piece bowl comprised of a tapering and vertical section, and its characteristically black spigot and matching hood.

Optical System

The opal Perpsex bowl acted as a diffuser, providing a symmetric light distribution around the lamp. The tapered

and vertical sections may have been designed to provide two separate diffused distributions, using the concept of

the Projected Area Principle, but I believe the lantern was designed along aesthetic lines by Ricks.

An alternative version was available with a 'pin-spot' Perspex bowl. This provided limited diffusion, softening

the non-axial asymmetrical distribution from a dome refractor mounted around a vertically mounted tungsten

or mercury lamp.

Gear

Initially gear was available for the low-pressure sodium and high-pressure mercury lamps 'mounted in the lantern

hood.' However, all the lanterns in collections have the gear mounted on the circular gear tray which held the lamp,

gear and the NEMA socket for the photo cell.

The Phosco P178 In My Collection

|

|

facing profile

I can't recall where this lantern came from. But it's in good condition with only some flaking of the black

paint around the spigot cap, and a small dent on the side of the hood.

|

|

|

|

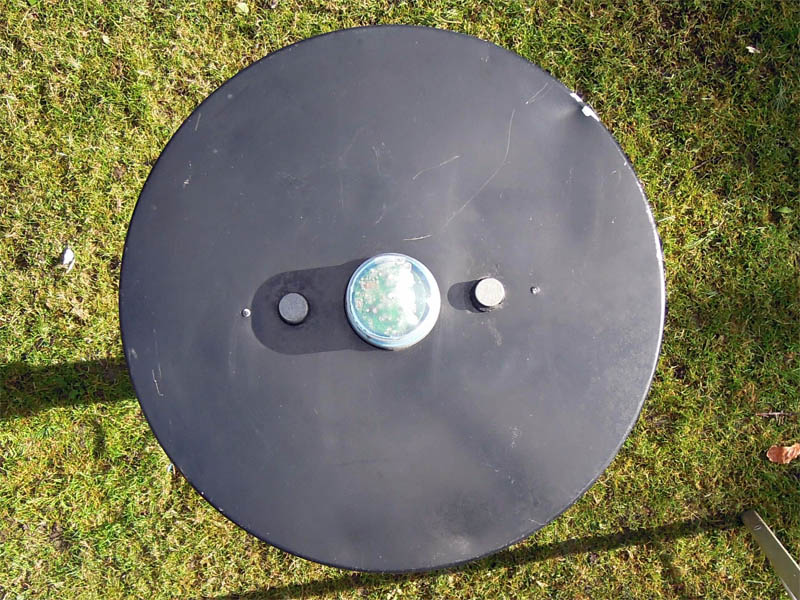

canopy

The aluminium spun hood is painted black and is held in place by two knurled screws. A large NEMA

socket for a photocell is positioned in the centre of the lantern. This is mounted on the gear tray inside

the lantern, and there's a round hole in the hood to accommodate it.

|

|

|

|

logo

There's no manufacturer's mark or logo anywhere on the exterior of the lantern.

|

|

|

|

pedestrian view

The one-piece Perspex bowl is complete and in good condition. Phosco used good quality plastics for these

lanterns, and the bowl doesn't show any signs of becoming brittle or discolouring.

|

|

|

|

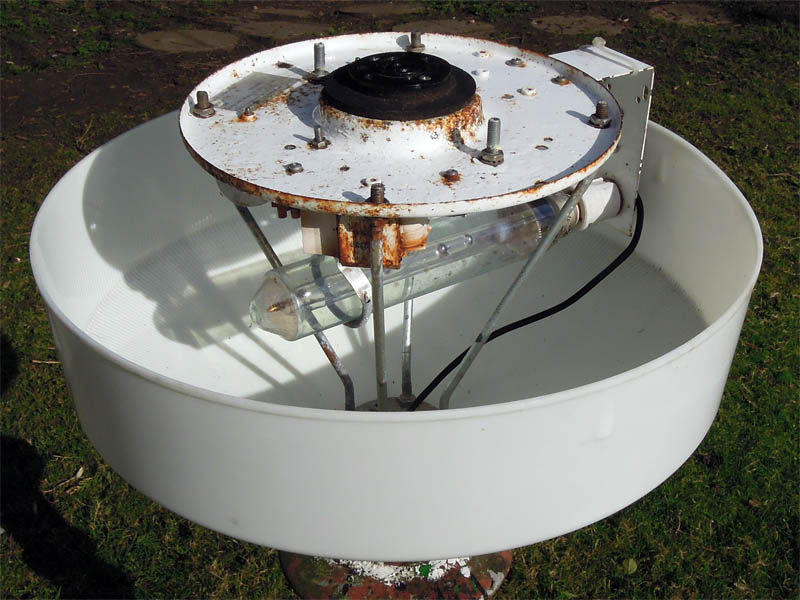

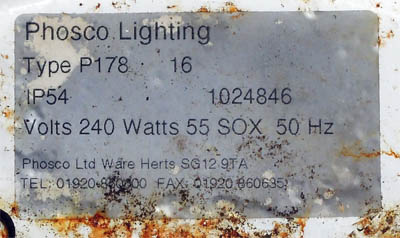

interior #1

The hood is removed by unscrewing the two knurled screws. A spindle, made from four cranked rods, supports

the gear tray which also houses the NEMA socket and the tapped holes to accept the knurled screws. The lantern

is fitted with a 35W SOX lamp but it's clear that it could accommodate the larger 55W size.

The lantern's identification sticker is mounted on the top of the gear tray.

|

|

|

|

interior #2

The spindle is bolted directly to the spigot cap and supports the weight of the gear tray and the hood.

The Perspex bowl itself takes very little weight.

|

|

|

|

interior #3

The gear is mounted on the underside of the gear tray, just above the lamp, lamp steady and lamp holder. The lantern

is fitted with a Parmar SZ355K245 Ballast, a Parmar PB055K245 ignitor and a

Cambridge Capacitors 6.5uF power correction capacitor which has a 08/04 date code.

|

|