|

Phosco P123 (SO 60/A3)

Genre: Enclosed Horizontal Traverse Low Pressure Sodium Lantern

The low pressure sodium discharge lamp was developed by Philips in 1932. After two successful trial installations

(including the first low pressure sodium installation in the UK along the Purley Way, Croydon) the first commercial installation

was installed by Liverpool Council in 1933 using specially commissioned lanterns from Wardle.

The development of lanterns continued through the 1930s and accelerated when it was determined that the lamp’s brightness and

its long length made it less susceptible to glare. Lanterns with bare bulbs suspended over an overhead reflector (the so-called "seagull" lanterns)

quickly followed. Glass manufacturers were initially slow as the first plate refractors for low pressure sodium lamps didn’t appear

until the end of the decade.

The advantages and disadvantages of low pressure sodium were readily debated, especially when an alternative (the medium and high

pressure mercury discharge lamp) was also available. The monochromatic light was considered especially useful for arterial

and traffic routes, the lamp’s shape cast a wide beam across the road surface, the light was also considered more penetrating

in foggy conditions and it was the most efficient light source being manufactured. However, the light was also considered

inappropriate for high streets, promenades, civic areas and residential streets and so some lighting engineers

restricted its use to traffic routes only. Therefore low pressure sodium became known as "the drivers’ lamp."

The arrival of plate glass refractors resulted in large lanterns made of metal frames enclosing heavy glass sheets.

These bulky lanterns continued to be made into the 1950s until being usurped by lanterns with plastic bowls and

machined or moulded plastic refractor plates. The lanterns were still large; the size dictated by the bulky

control gear, but their design and construction was becoming simpler.

The 1950s and 1960s saw huge improvements in the construction and efficacy of low pressure sodium. Early two-piece

designs (dubbed SO) were replaced by the one-piece, more efficient integral design (called the SOI). The development of

linear sodium (SLI) broke the one hundred lumens per watt barrier, lead to a radical rewriting of the British Standards

of street lighting and prompted the development of new families of streamlined lanterns. But it wasn’t until the arrival

of a new heat-reflecting technology (called SOX) that a cheap family of extremely efficient bulbs became available.

The energy crisis of the 1970s saw a rethink in street lighting and lamp efficiency became dominant when fuel was both

in short supply and expensive. This saw the large scale removal of colour corrected high pressure mercury, fluorescent and

ancient tungsten lamps by low pressure sodium replacements. The old arguments that the smoky-orange lamps were inappropriate

for residential areas no longer applied. By the end of the 1980s, low pressure sodium was the dominant street lighting lamp used in the UK.

The use of low pressure sodium came under scrutiny again. High pressure sodium, finally developed as a viable technology in the

1960s, was coming of age and offered a compromise of slightly less efficacy with better colour rendering. Questions were

being asked about the physiology of the eye and visual adaptation under low lighting levels; previously the wavelength

of low pressure sodium had been deemed the most suitable, but research now suggested that the eye responded better to white

light. Concerns were raised about light pollution and the low pressure sodium lamp was seen to be the chief culprit

(although it was more to do with older non-cutoff and semi-cutoff optical designs rather than the lamp itself).

By the turn of the century, the age of low pressure sodium was seen as coming to an end. Research in white light technologies,

especially metal halide and a renewed interest in compact fluorescent coupled with the advantages of using white light at

low lighting levels, saw the end of the low pressure sodium lamp’s dominance. Its use was discouraged in the specifications,

lantern manufacturers started to wind down their production and bulb manufacturers followed suit.

By the end of the first decade of the 2000s, low pressure sodium was in stark decline, and less and less of the UK’s

streets were being lit by its characteristic orange glow.

Name: Phosco P123 (SO 60/A3)

Date: Mid 1950s - Mid 1960s

Dimensions: Length: 18 7/8", Width: 12 3/8", Height: 9 ¾"

Light Distibution: Non Cut-Off (BSCP 1004 Part Two:1956)

Lamp: 35W SOX

History

|

|

By the mid 1950s, the rebuilding of the UK’s infrastructure was proceeding at full speed, and many new companies

appeared who were eager to pick up the various lucrative relighting contracts. Phosware (later Phosco) were founded by

Concrete Utilities; the firm were experiencing unprecedented demands for their concrete columns (as the use of steel for street lighting

was still restricted) and decided to branch out into lantern manufacturer as well.

Their first low-pressure sodium lanterns were simple open-types, but the firm soon developed a family of enclosed low-pressure sodiums. This

family were typified by their aluminium canopies, wide and deep Perspex bowls (designed to accommodate the huge bulky gear of the era),

vertical refractor grooves at the end of the bowls, and overhanging lip which accommodated the “Oddie Key” (a unique bowl fastening mechanism

only used by Phosco).

The lanterns were initially quite successful and were featured in many of Phosware’s advertisements. The main road version, designed to

take 85W-140W SO/H (later 90W SOX) was the most successful, but the smaller side road versions also saw service.

By modern standards, the lanterns were huge. As soon as gear sizes were reduced, Phosware were quick to replace the range with the P152

series; this shared the characteristics of the earlier family but were smaller. This allowed Phosware to cut down on raw material costs

for manufacturing. For a while, both ranges were advertised side-by-side (particularly in the early 1960s), but the P120 range

was gradually run down and discontinued.

The P123 was the top-entry version of the lantern, designed to take a 60W SO/H bulb. The lantern was also known as the SO 60.

|

Popularity

The smaller wattage lanterns in the range (the P120 through to the P123) were not as popular as the

larger wattage versions. However, their smaller replacements (the P152 series) were far more popular and saw service

throughout the country.

Identification

The lantern is easily identified by its size and profile. Furthermore the vertical grooves in the end of the bowl and the use of an

Oddie key are unique PhosWare characteristics. Additionally, the lantern’s manufacturer and early model number are

cast into the lip (which was space required by the Oddie key mechanism).

Interestingly the model number is given as “SO 60 A/3”. The model in Mike Barford’s collection is the top-entry P122 and has “SO 60” cast into the lip.

Optical System

The optical system is interesting as the bulb is positioned at the base of the bowl. The refractor plates are positioned

centrally and only form the main beams from light cast upwards by the bulb or from reflected light from the overhead

reflector. In this way, the overhead reflector is far more important in this lantern than it normally is in other low-pressure

sodium lanterns where the bulb is positioned in the centre of the refractor plates.

The vertical refractors at the end of the lantern are designed to spread the flux in azimuth.

The interior of the canopy is also painted white, but this secondary optical system only reflects a fraction of the flux as most

is reflected by the overhead reflector.

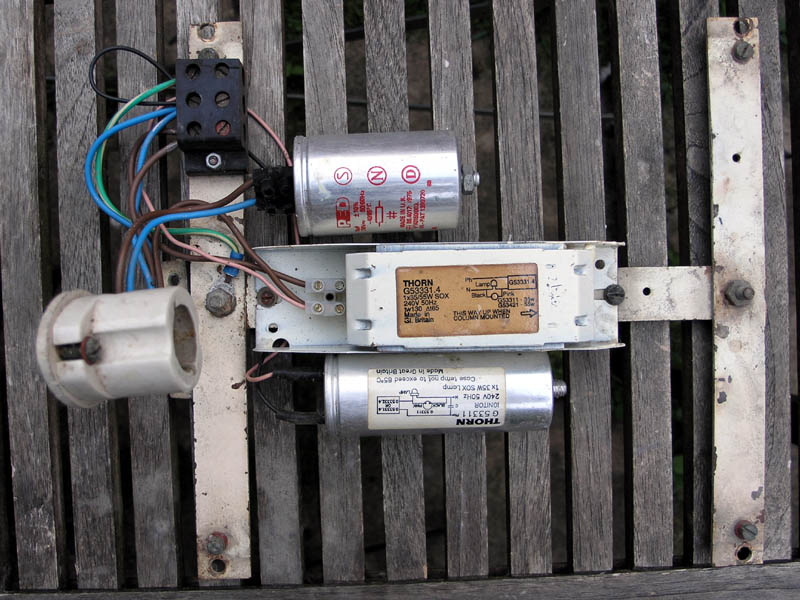

Gear

The lantern was originally designed to take the huge leak transformer and square condenser being produced in the early 1950s

(hence the requirement for such a large lantern). These were mounted back-to-back on a metal chassis which was bolted to the

canopy of the lantern in turn.

|

|

|

facing profile

I have never discovered any large installations of this lantern (a lone cul-de-sac in Royston is lit by them) but they were used

for exterior lighting at Rauceby Mental Hospital near Sleaford in Lincolnshire. A sizeable number were fixed to

the main hospital buildings and used to light the main drive.

|

|

|

|

front profile

This shot clearly shows the vertical refractor grooves at the end of the lantern. This was a PhosWare standard

design for all their early lanterns. It was designed to spread the flux in azimuth, spreading the small amount of light

emitted from the ends of the bulb.

|

|

|

|

trailing profile

Despite years in service, the lantern was still in good condition. The bowl was still clear; the interior required some

repainting and the canopy still bore traces of the original bronze paint. Being privately owned, the lantern was never

fitted with a photocell and was probably group switched.

|

|

|

|

canopy

The bowl was secured by one Oddie key situated at the street end of the lantern. As this required space (for both

the key and its engaging mechanism), the end of the canopy extended slightly past the bowl, which gave the lantern its unique appearance.

|

|

|

|

logo

There were no maker’s marks or logos on the top of the canopy. The original bronze finish has only just started

to wear away, exposing the silver aluminium.

|

|

|

|

pedestrian view

The three key areas of the refractor bowl can be seen in this shot: the vertical grooves at the bowl ends to spread

the light emitted; the main refractor panels which fashioned the two main beams; and the frosted base which acted as a diffuser

and scattered the light emitted below the lantern.

|

|

|

|

vertical

This shot clearly shows how the Perspex bowl was placed in a metal holder which was secured by an Oddie

key at the street end of the lantern and hinged at the house end. The makers’ name and lantern model number can just be seen

in the extruded area of the canopy by the Oddie Key.

The lantern has since been fitted to a BLEECO Brighton C bracket.

|

|

|

|

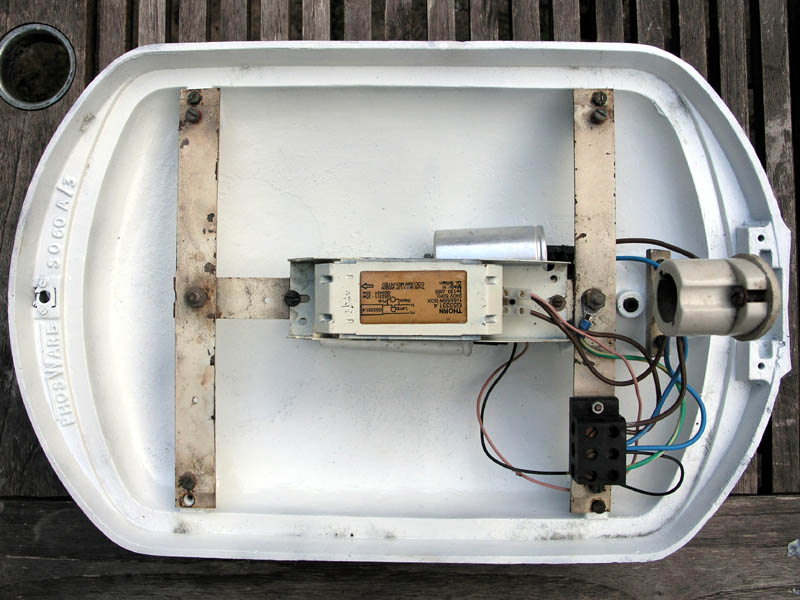

interior #1

The interior of the lantern was extremely simple with two screw holes for the bulb assembly, two screw holes for the two securing

Allen keys and four screw holds for the gear support chassis and over reflector assembly.

The lanterns maker and model number can be clearly seen: "PhosWare SO 60 A/3". It’s known that the "PhosWare SO 60" was the top

entry version, but it isn’t known what differentiates the "A/1", "A/2" and "A/3" models.

|

|

|

|

interior #2

The gear chassis originally took a large leak transformer and square condenser mounted back to back. However, these had been

replaced by modern gear. A Thorn G53331.4 transformer, PED capacitor (dated 1988) and

Thorn G53311 ignitor are now in-situ; the transformer is fitted to the chassis but the other two

cylindrical components are loose and rest on-top of the over-reflector.

|

|

|

|

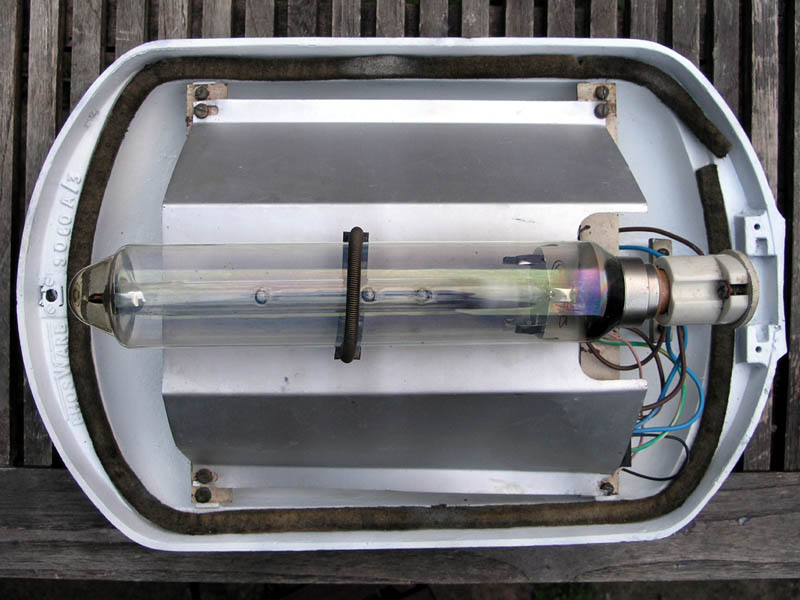

interior #3

This shot shows the metal chassis in place. The black terminal strip isn’t standard either, probably being installed

when the new gear was added. This wasn’t well thought through when it was fitted (as will be seen below).

The over-reflector is secured to the lantern by four screws attached to the gear chassis. The over-reflector

also carries the sprung lamp steady.

|

|

|

|

interior #4

Thanks to the new terminal strip, the over reflector can’t be fitted to the lantern properly. The electrical engineer tried to bend it

but left the lower right corner unfixed instead.

|

Phosco P123 (SO 60/A3): Night Burning

Phosco P123 (SO 60/A3): As Aquired

Rescued from Rauceby Hospital where this was the lantern of choice in the grounds, this was one of Phosco's

earliest small sodium lanterns.

A gear-in-head design, the old gear has long gone, replaced with modern gear to run SOX-E.

The Phosco P123 was used extensively for exterior lighting at Rauceby Mental Hospital. The roadways were lit

by these lanterns on Concrete Utilities concrete columns whilst many wall mounted lanterns were attached to the hospital buildings themselves.

This lantern originally lit the entrance to the engineering courtyard. This picture shows it in-situ: it's the closest

lantern (its partner to the back is a Phosco P153 and is also in the collection).

It was removed with permission by Bloom Demolition.

|